Learn how Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act sets up a framework for handling the adverse effects of government undertakings – and how Preservation Maryland uses these tools to save places that matter.

Established in 1966, the National Historic Preservation Act created the basis for the modern historic preservation movement – from the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation to the National Register of Historic Places to Section 106.

HOW SECTION 106 WORKS

Section 106 has been one of the most important tools to originate from the Act. This law requires Federal agencies to take into account the effects of their undertakings on historic properties, and afford the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation a reasonable opportunity to comment. Fortunately, Maryland also has its own version of this law, commonly referred to as “State 106,” legally defined as Sections 5A-325 and 5A-326 of the State Finance and Procurement Article.

Put plainly, these laws require that federal and state undertakings like spending funds, issuing a permit, transferring a property, and other actions be reviewed by the State Historic Preservation Office to determine if there is an adverse effect. If an adverse effect is found, the agency causing that effect must consider the impact and work with consulting parties, like organizations, citizens, neighbors, and local governments, to avoid, minimize or mitigate the impact.

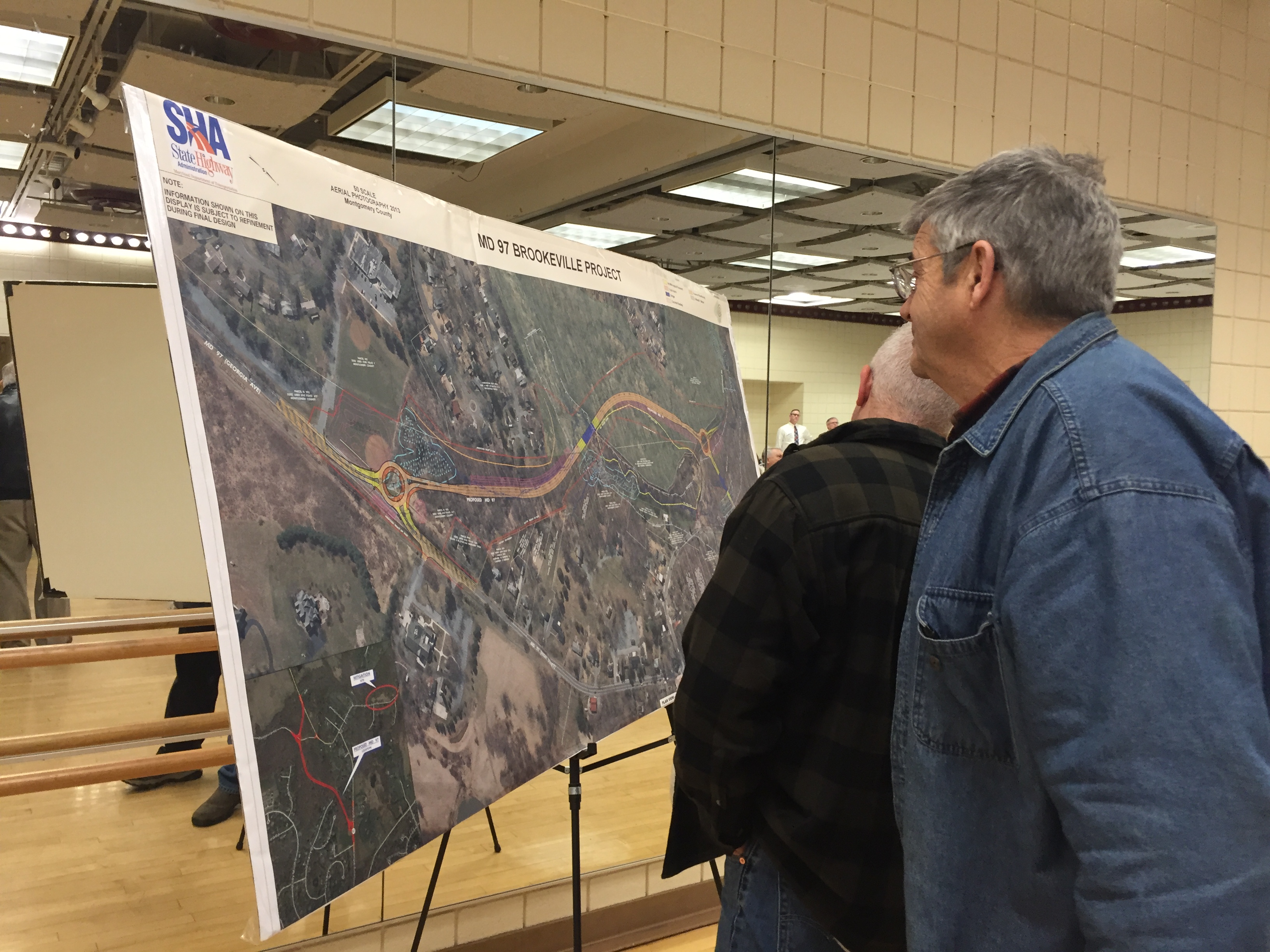

Section 106 in progress at Brookeville, Maryland

The process of identifying potential mitigation strategies and “resolving adverse effects” is commonly referred to as consultation. Consultation usually results in a Memorandum of Agreement (MOA), which outlines agreed-upon measures that the agency will take to avoid, minimize, or mitigate the adverse effects.

WHEN WE GET INVOLVED

The Maryland Historical Trust reviewed nearly 5,400 projects in 2015 – with only a few dozen resulting in an adverse effect that required consultation.

Preservation Maryland cannot engage in every consultation, but when the stakes are high, the precedent is troubling or the scale of the project is vast, we do get involved. We are currently actively involved in several significant consultations, including: The construction of a bypass around historic Brookeville in Montgomery County, the $700 million vacant housing demolition effort in Baltimore City called Project C.O.R.E., and the B&P Tunnel project in Baltimore City.

We take our role seriously and when the loss of historic resources cannot be avoided, we push for creative, lasting and impactful mitigation. Mitigation can come in many forms – including survey, research, documentation, interpretation, bricks-and-mortar funding, staff assistance and more.

To learn more about Section 106 and how you can play a role as a citizen or organization, visit the website of the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation.