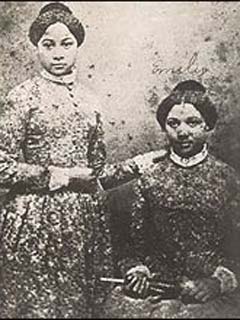

The Edmonson siblings are most well known for their daring attempt at escape on the Pearl in 1848. Although there are four older brothers, the two young sisters, born in Montgomery County, are are at the forefront of the story. Most of their older siblings had successfully bought themselves out of slavery either by themselves or with the help of a future spouse. Their enslaver refused to let any more siblings free themselves, which led to the drastic actions the siblings took.

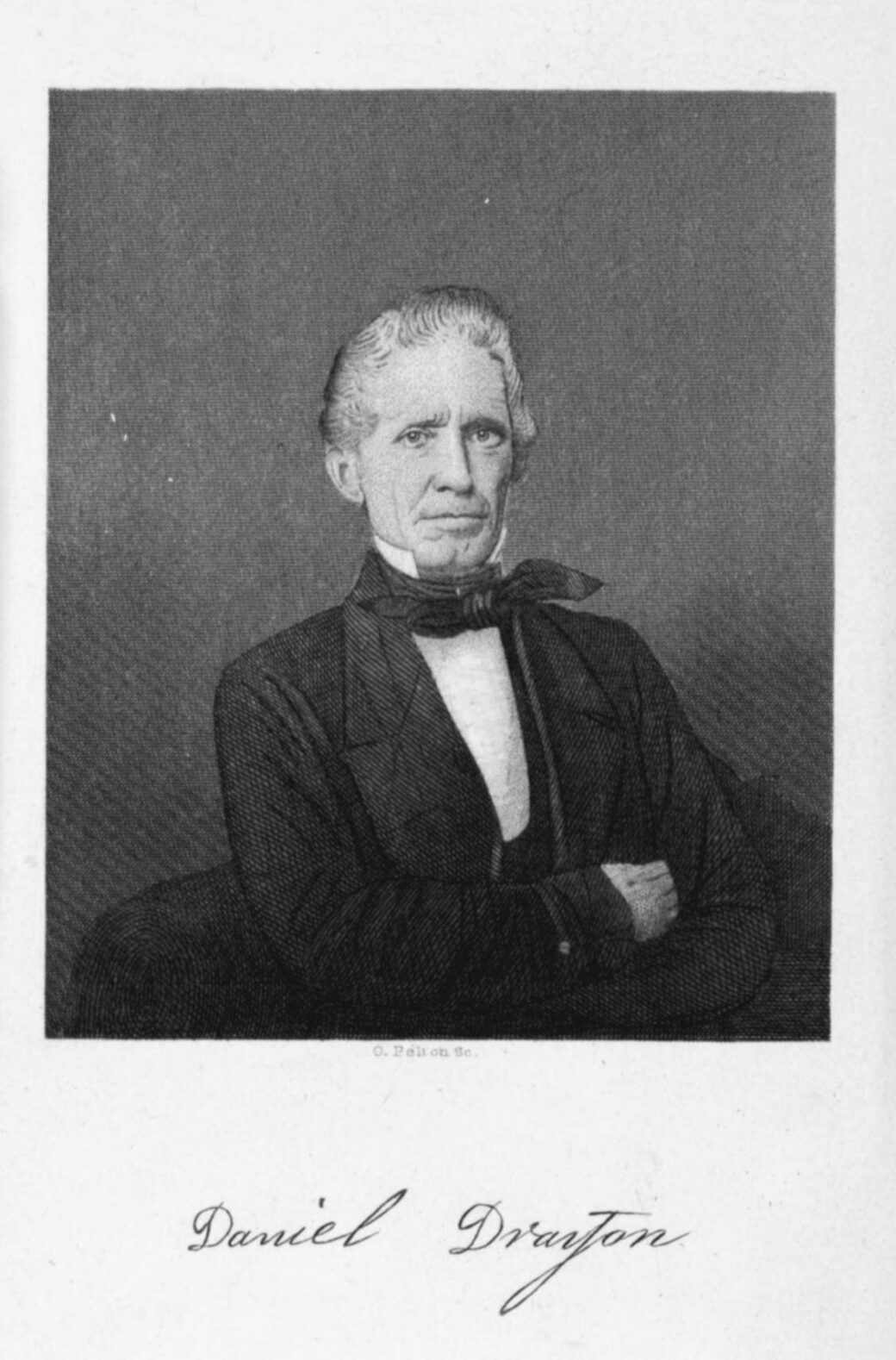

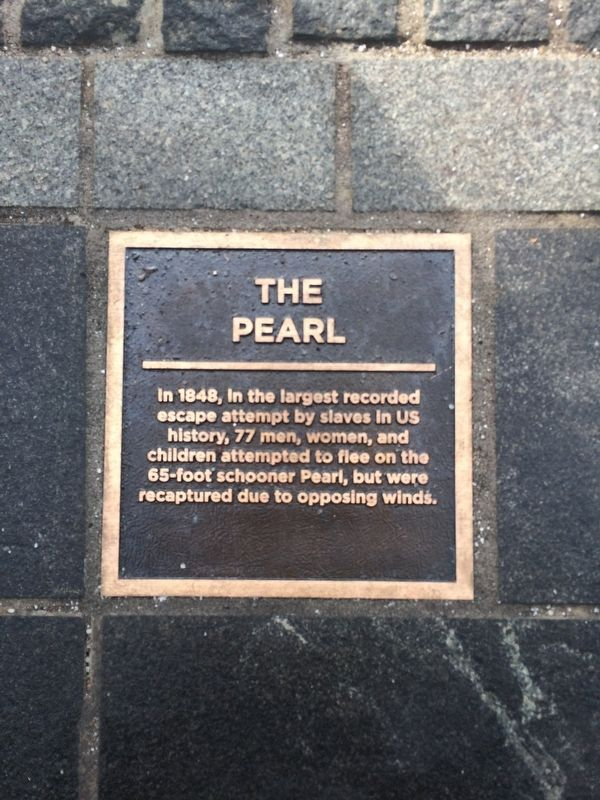

Samuel Edmonson was said to be the one who convinced the rest of his siblings to take their risky journey. After listening to an address by Senator Patterson of Tennessee and Senator Foote of Mississippi, he was inspired. Soon, he was informed of Daniel Drayton and Captain Edward Sayres, men who were willing to take a group in their ship, The Pearl, and bring them to New Jersey. A group of seventy-seven slaves were organized, including four Edmonson brothers (Ephraim, Richard, John, and Samuel) and two sisters (Mary and Emily). The brothers ranged from the ages of about 30 to 18, with Samuel being the youngest. The sisters, fifteen-year-old Mary and thirteen-year-old Emily, were initially hesitant, but after a conversation with their mother where she urged them to seize their chance, the two joined with the group. The group set out that night, successfully making their way out of Washington D.C.

Two days later, the group was caught and captured. John H. Paynter, a descendant of the Edmonsons, wrote in his description of events: “Captain Drayton and his mate were immediately the storm center of the infuriated masters, many of whom were loud in the demand that summary vengeance be wreaked upon them and that these two at least should be hung from the yardarm.” The men were ready to inflict violence on the group, but before they could, Richard Edmonson, the older brother of Samuel, Mary, and Emily, “bounded on deck and in a voice of suppressed excitement exclaimed, ” Do your-selves no harm, gentlemen, for we are all here!'” His loud actions in the dark frightened the men and made them hesitate. Once the enslaved had all arrived on deck, a man from the mob went to strike Samuel but was sabotaged by a sudden lurch of the ship, causing the blow to hit the side of his head instead. Drayton and Sayres protested the violence, and the mob relented, potentially saving lives and preventing heavy injuries. Still, the group was crushed.

Paynter recounts:

“Among them then there were but few who were not completely crushed, their minds a seething torrent, in which regret, misery and despair made battle for the mastery. Children weeping and wailing clung to the skirts of their elders. The women with shrieks, groans and tearful lamentations deplored their sad fate, while the men, securely chained wrist and wrist together, stood with heads dropped forward, too dazed and wretched for aught but to turn their stony gaze within upon the wild anguish of their aching hearts.”

Upon arriving in Washington, they were met with a mob. An Irish man attacked Drayton with a dirk and cut off part of his ear. Allegedly, an onlooker said to Emily, “Aren’t you ashamed to run away and make all this trouble for everybody?” To this, she replied, “No sir, we are not and if we had to go through it again, we’d do the same thing.” John Brent, the husband of the siblings’ older sister, received an agreement from the administrator of the estate that owned the siblings that they would have an opportunity to purchase them. However, the very next day, he sold them to Bruin and Hill, the slave dealers of Alexandria and Baltimore. He received $4,500 for the six of them. Bruin refused to listen to the pleas of the other siblings and family members and instead said that “he had long had his eyes on the family and could get twice what he paid for them in the New Orleans market.

The siblings were taken to Alexandria and lived in squalid conditions where the sisters were forced to do washing over a dozen men. They were there for a month before they traveled to Baltimore, where they stayed for a further three weeks. While there, the family was able to raise enough money to purchase Richard’s freedom (he was prioritized due to a sick wife and children); they were already on the water, and the trader refused to bring Richard back to shore. They sailed to New Orleans, a horrifying move as slaves were more poorly treated in the South. The siblings suffered poor conditions and extreme seasickness. Emily had the worst case, and for a time, her brothers feared she might die. However, she was well cared for by her siblings and pulled through.

Their arrival only brought more horrors for the siblings. The girls were made to stand in the showroom, where people thinking of purchasing them could examine them. Harriet Beecher Stowe, author of “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” and friend of the family, described the scene: “The siblings were made to stand in an open porch fronting the street for passers-by to look at.” She goes on:

“Whenever buyers called, they were paraded in the auction room in rows, exposed to coarse jokes and taunts. When any one took a liking to any girl in the company, he would call her to him, take hold of her, open her mouth, look at her teeth, and handle her person rudely, frequently making obscene remarks; and she must stand and bear it, without resistance”.

This treatment continued until the brothers advocated for the girls to Wilson, a partner of Bruin and Hill who was in charge. After the conversation, the girls were treated “with more decency.”

Hamilton, an older brother of the siblings, had attempted escape, been caught, and sold down to the south sixteen years ago. Richard’s status as a free man allowed him to search for their brother and to request his help. Luckily, Hamilton had just purchased his own freedom for $1000. Richard was able to find him and bring him to the prison. He had never met Emily; she was born after he was sold. The meeting between the siblings was emotional, with Paynter describing Hamilton’s reaction as “joy, though mingled with sorrow.” After word was incorrectly sent that the family back home had raised half the money for the girls, the traders allowed the girls to spend the night at Hamilton’s house instead of the small room shared with 20-30 women where they slept on the floor. Hamilton was also able to find a kind buyer for Samuel.

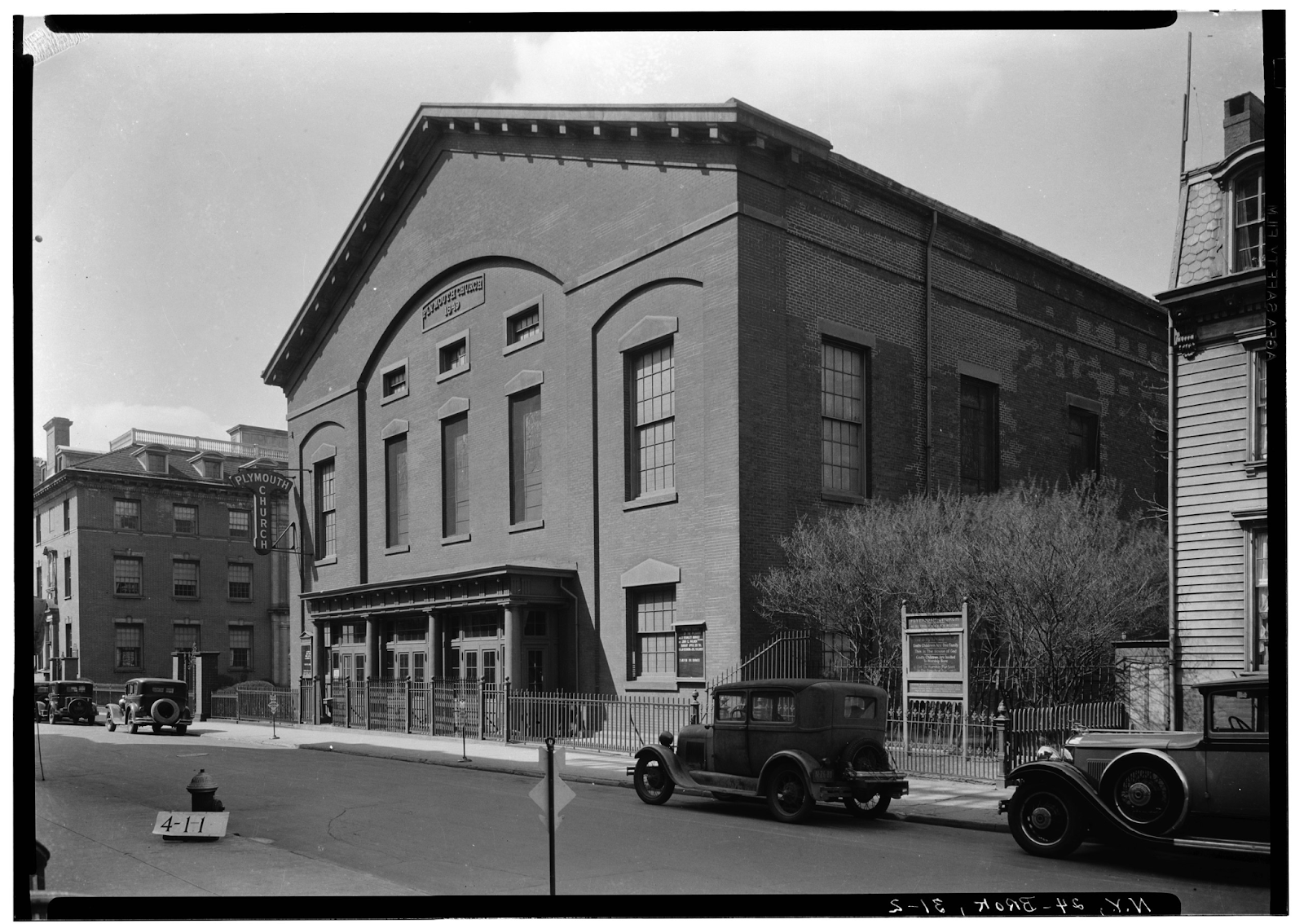

The Yellow Fever epidemic caused the traders to take the siblings (without Samuel) back to Baltimore to prevent the loss of the enslaved and, therefore, profit. They were placed in the same prison as before, and Richard was officially freed. Paul Edmonson, the father of the siblings, visited them, and after weeks of talks, he was able to get an agreement to buy the sisters for $2,250 if the amount was raised in a certain time period. So, off Paul went, trying to raise the money to save his children. His first stop at the anti-slavery office was unsuccessful. His next attempt was on Reverend Henry Ward Beecher, the sibling of their future friend, Harriet Beecher Stowe. He pleaded his case, convincing the reverend to help him raise the money. He told Paul of a public meeting that would happen that night. So that evening, the reverend “spoke as if he were pleading for his own father and sisters,” and the money was raised on the spot.

The sisters, meanwhile, under the care of Mr. Bruin, were treated “with as much kindness and consideration as could possibly consist with the design of selling them.” He was friendly but also wasn’t willing to lose the money by freeing them outright. On the day their father showed up at the house, the girls were filled with both elation and trepidation. Elated to see their father but trepidatious because they were afraid he didn’t have the money. Luckily, he did, and the girls were finally freed.

The Brooklyn church of Rev. Henry Ward Beecher, which had previously helped them raise the money for their freedom, continued to contribute money so the sisters could attend school. During their studies, the sisters traveled to New York to participate in anti-slavery rallies. The sisters also attended the protest convention in Cazenovia to protest against the Fugitive Slave Act. Fredrick Douglass led the convention, declaring “all slaves to be prisoners of war and warned the nation of an unavoidable insurrection of slaves unless they were emancipated.”

Later, the sisters were able to attend the Young Ladies’ Preparatory School at Oberlin College through the continued support of Rev. Henry Ward Beecher and his sister. During this time, the sisters exchanged letters with Harriet Beecher Stowe, some of which still survive.

Unfortunately, at only 20 years old, Mary died of tuberculosis. Emily was heartbroken, leaving Oberlin for the Normal School for Colored Girls in D.C. She writes in a letter to a friend, “Though she is gone from me, it seems as though, I could see her all the time, in my dreams, and when I am awake, and hear her gentle voice speaking to me.”

Emily’s studies at the Normal School for Colored Girls prepared her to be a teacher. Due to hostility towards the school, Emily, along with Myrtilla Miner (pictured below), the founder of the school, were taught to shoot to protect themselves and the students. Emily was able to teach and continue her abolitionist work.

At twenty-five, Emily married widower Larkin Johnson and became stepmother to his four children. Together, they had an additional three children. They lived in Sandy Spring, Maryland, for several years before moving to Washington, D.C., where they helped establish the Hillsdale Community. Emily maintained her relationship with Frederick Douglass. One of her granddaughters said of the relationship,

“Grandma & Frederick Douglass were like sister and brother—great abolitionists. I sat on his knee in his office in the house that is now a museum in Anacostia, where we were born.”

Emily Catherine Edmonson Fisher Johnson was a force in the fight against injustice. While her daring escape is famous, her actions afterward are what really make her an important contributor toward equal rights and fair treatment. From participating in big anti-slavery rallies to teaching children, Emily was a force for progress. She died September 15, 1895, seven months after Frederick Douglass. The sisters have a bronze statue in Alexandria, Virginia, erected in 2010.

Special thanks to Wikitree, who compiled detailed biographies with sources of the Edmonson family to keep Black heritage alive; to Harriet Beecher Stowe and John H. Paynter, whose writings were referenced heavily in this post; and the Archives of Maryland, where several of the biographies of the Edmonsons live.

Content for this blog was compiled with the help of our Waxter Intern Miel Hunt. Miel is a recent graduate of the Ithaca College Park School of Communications. Raised in Texas, France, and Maryland, her multicultural upbringing opened her eyes to new perspectives and ignited her passion for history and storytelling. She is thrilled with the opportunity to combine those interests with Preservation Maryland. Having lived 5 years in France, she speaks French and is a bit of a Francophile particularly concerning French history. However, after over a decade in Maryland, she is proud to call it her home.