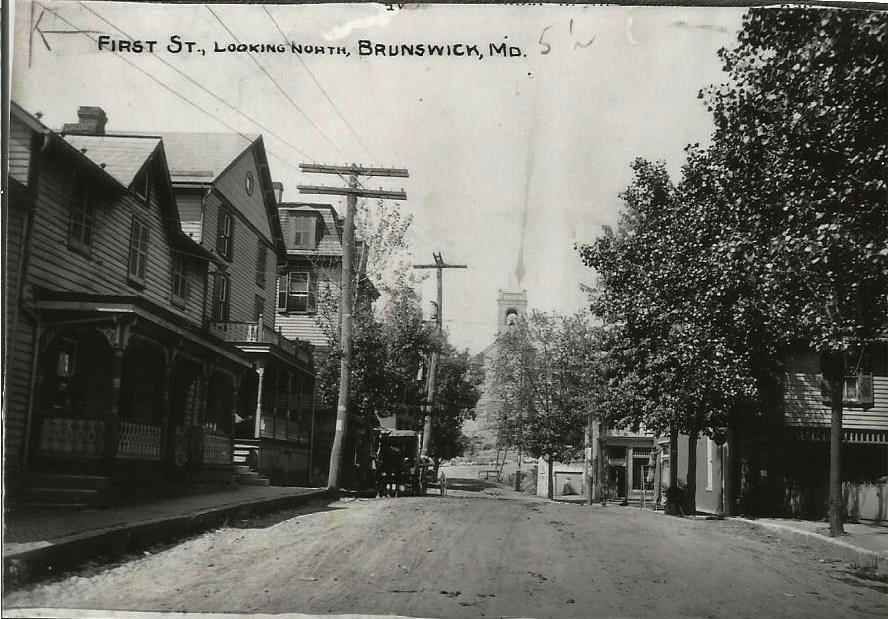

Featured image: The Berlin house circa 1900, when S. Maple Avenue was known as Third Street. The postcard misidentifies the street. Image courtesy of the Brunswick History Commission. Image directly above: The Berlin house in 2023. While some changes are evident, such as the removal of the central window on the second story, the building is largely the same.

If you’ve been following Preservation Maryland over the last few years, you’ll know that our Historic Property Redevelopment team has been hard at work managing brick and mortar preservation projects across the state. Among them is the rehabilitation of the Berlin House at 9 South Maple Avenue in Brunswick, Maryland. The main block is a two-story, three-bay, detached vernacular house with a three-bay front porch. The side-gabled roof features a pointed wall dormer on the southeast façade. A rear addition creates an overall L-shaped plan. It is believed to be one of the oldest structures in the city and one of only a handful of extent structures from when the town was known as Berlin. The town changed its name to Brunswick around the turn of the 20thcentury.

The property served as home to generations of families and individuals until 2005. It has since sat vacant and was identified as a structure to be saved and rehabilitated for public use through the Section 106 process initiated in 2020 as part of Brunswick’s larger Railroad Square redevelopment project. Preservation Maryland is partnering with the City of Brunswick to protect and rehabilitate the historic house.

Our team has spent the last few months digging into the history of this unique structure, reading through pages of digitized deeds, maps, wills, and census records and travelling to state archives and county clerks’ offices to uncover and understand the building’s life and the lives of its occupants before its current stewardship. These stories, pieced together through a variety of primary and secondary sources, help inform the preservation and interpretation of the site. Our blog today explores our findings.

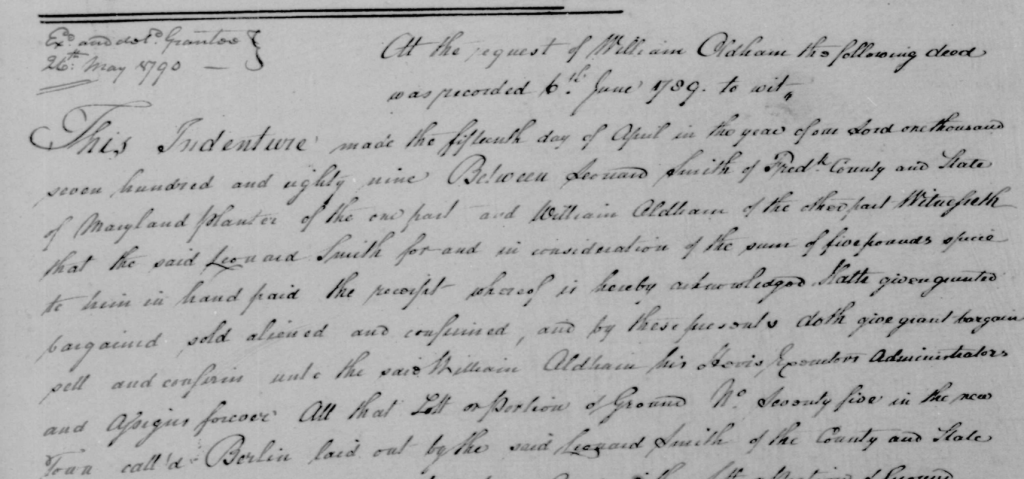

Our research began with deeds so that we could create a full chain of title for the property. We were able to trace the property back to Leonard Smith, who purchased the larger parcel of land which would become the town of Berlin and subdivided it into several lots. In 1789 Smith sold lot number 75 (on which the Berlin house now sits) to William Oldham with the stipulation that he “build a Log or Framed House on the said lott not less than twenty feet long and sixteen feet wide with a Stone or Brick Chimney.” This seemingly small inclusion is important for our research. It reveals possible original materials of the house and indicates a possible date of construction, valuable pieces of information when creating a preservation plan for a structure.

1789 deed showing the transfer of the Berlin house lot from Leonard Smith, proprietor of the Town of Berlin, to William Oldham.

We were not able to find a document confirming that Oldham did indeed construct a house, but a deed dated 1842 specifies the sale of “a house and two lots of ground,” so we can narrow the period of original construction between 1789 – 1842. Over the next two centuries, the property passed through fifteen different owners before being given to the City of Brunswick in 2023

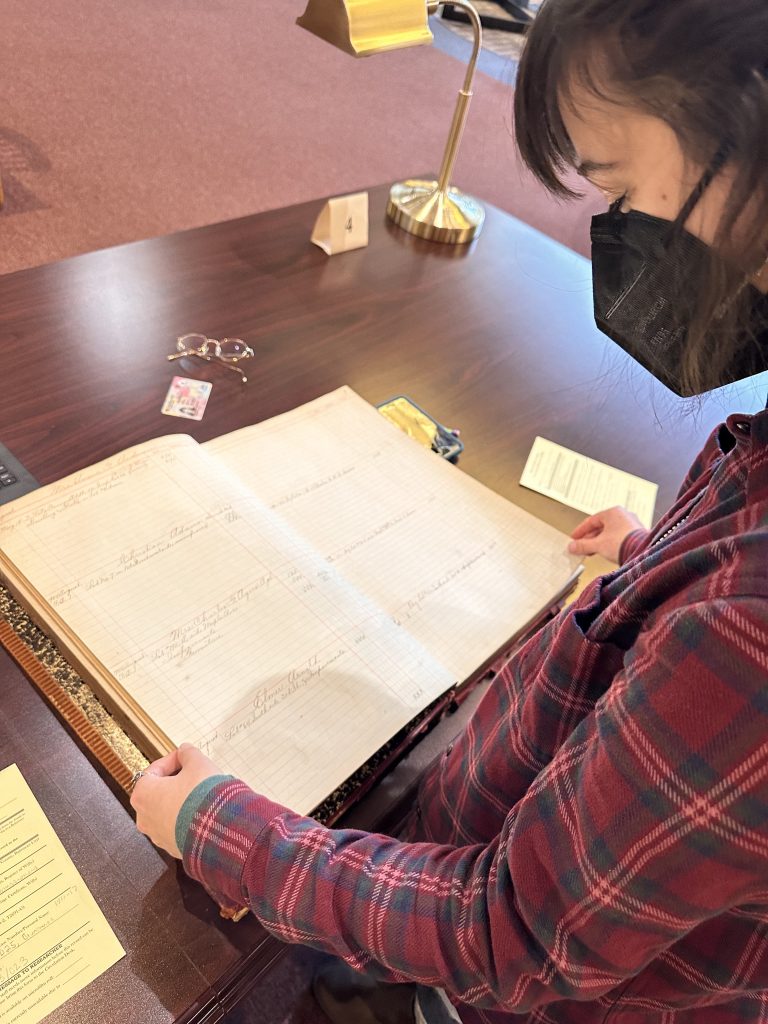

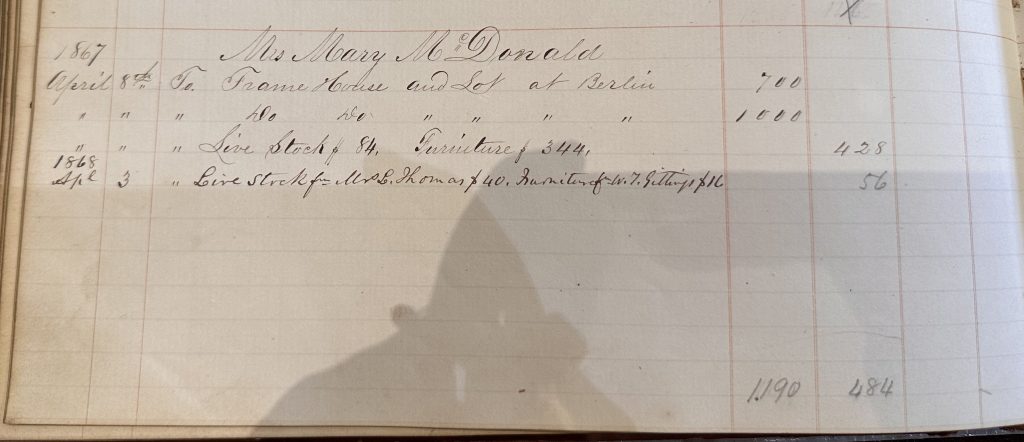

Left: Preservation Maryland Revitalization Specialist, Maggie Pelta-Pauls, reviews property tax documents at the Maryland State Archives in Annapolis. Right: 1866 Property tax assessment for Mary McDonald, owner of the Berlin House from 1865 until her death in 1911. The document indicates she owned two frame houses, livestock, and furniture and details the value of her property in the right-hand column.

In some cases, property tax assessments can provide information on construction date, building type and material, as well as alterations to a structure, by comparing the change of property values and amount of tax owned over time. Once the chain of ownership is established through deed research, the owner can be looked up in tax assessment records, which are organized by year. During this time period in Frederick County, tax rolls included the owner’s name, a description of their property, including livestock and furniture, and the assessed value of said property. The assessments we found for the Berlin house were not particularly detailed but did confirm that the house was of frame construction.

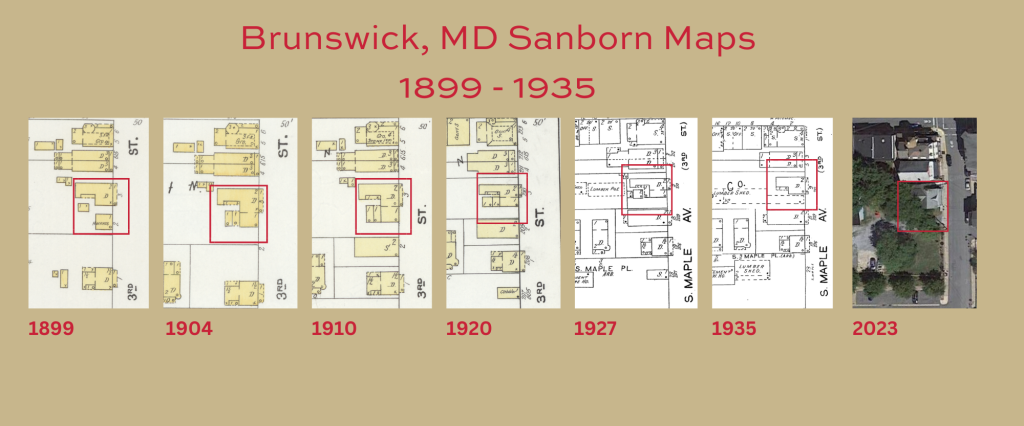

Another vital piece of information documented in the deeds is that South Maple Avenue in Brunswick used to be known as Third Street in what was then the town of Berlin. This is crucial for continuing the property research through maps. One excellent collection of resources is Sanborn fire insurance maps. Created by the Sanborn Company, these are detailed maps of cities and towns intended to be used by insurance companies to assess their total liability. They contain information on construction materials, approximate building size, and general building use.

The oldest Sanborn maps for the town of Berlin date to 1899. The 1899 map indicates a two-story, frame dwelling with a rear addition and front porch on Third Street. This confirms that the home was originally of frame construction and helps us date the addition to 1899 or earlier.

Brunswick Sanborn maps depict changes on lot 75 from 1899 – 1935. The Yellow color indicates frame construction, the “D” indicates a dwelling, and the number two in the top right corner of the structure indicates two stories. Sanborn Maps courtesy of the Library of Congress.

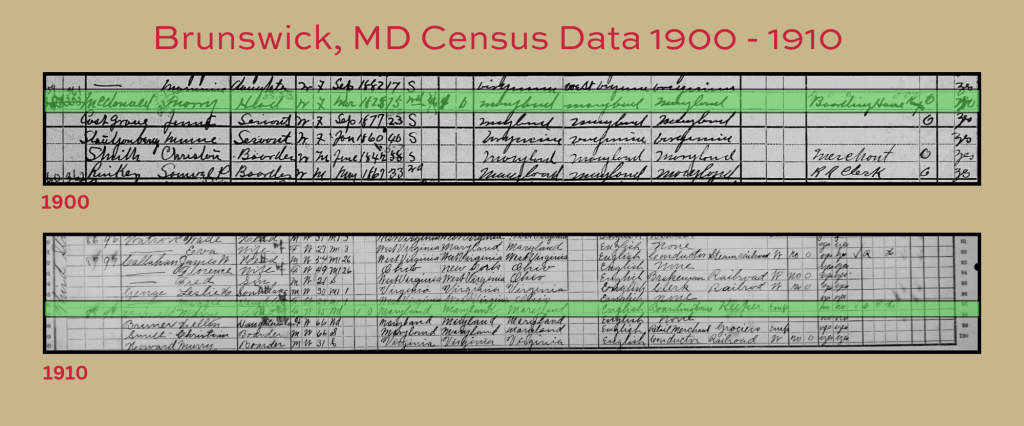

While deed records provide information on the chain of ownership and Sanborn Maps can illustrate building change over time, we must turn to other sources to piece together a more complete social history of the house. Census data and newspapers can help fill the gap regarding possible residents and connected events. It is important to keep in mind, however, that even these sources are not exhaustive. Census data, in particular, is just a snapshot. It captures who was at the house at a specific moment in time. Just as census data is collected today, information was self-reported and can be incomplete and/or inaccurate.

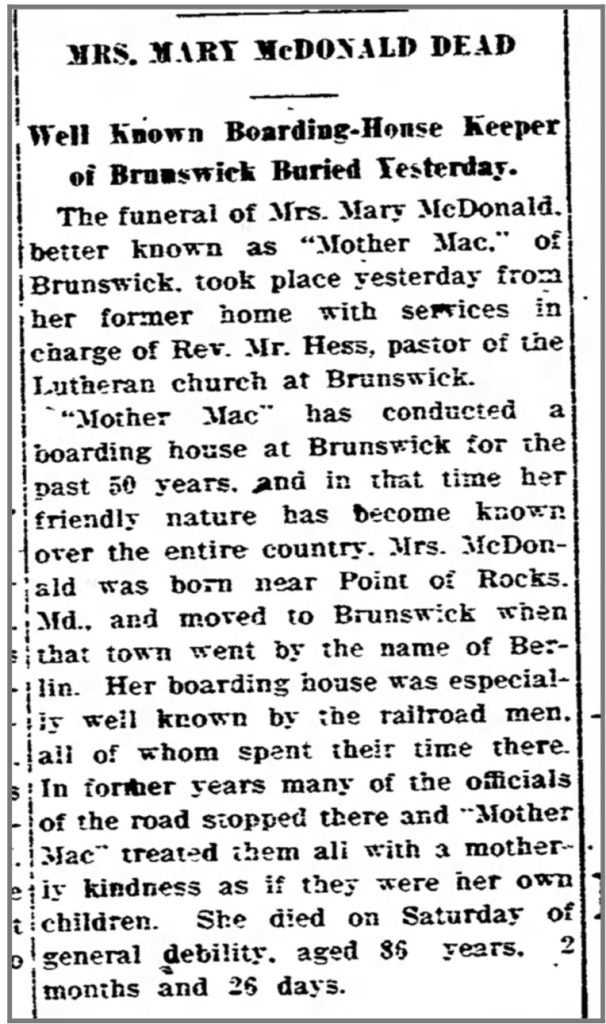

That being said, census and newspaper research on the Berlin house revealed that it was used as both a single-family residence and boarding house over the years. For example, Mary McDonald, who owned the property from 1865 to 1911, was a well-known community member and operated a boarding house for railroad employees for over 50 years. Mrs. McDonald’s boarding house is actually reflected in both the 1900 and 1910 censuses, which indicate at least two railroad workers as boarders in the house at the time of the census-taking.

Each obituary we found for Mrs. McDonald, which were printed across multiple regional newspapers, including The Baltimore Sun, references her boarding house. They indicate that she cared for her boarders as if they were her own, with one noting that railroad officials made a point to stop at her house for “some of her famous mince pies and apple dumplings” whenever they visited Brunswick.

Pictured Left: Mary McDonald’s 1911 obituary in The Frederick Post on July 5th. She was well-known by railroad workers throughout the region. Her hospitality earned her the nickname “Mother Mac.”

Census data from 1900 and 1910 provides sheds light on the tenants of the Berlin House. Mary McDonald highlighted in green, is listed as a boarding housekeeper. She had at least three different tenants over the decade. One of them was a merchant who is listed in both censuses. The other two were railroad employees, a clerk and a conductor. The 1900 census also lists two servants in the household, revealing that McDonald had enough income to hire domestic help. Census data from the National Archives and FamilySearch.org.

Our research on the Berlin house revealed not only the history of the building itself, but also snapshots of Brunswick over two centuries. As preservationists, one of our primary goals is to use this historical documentation to form as clear a picture as possible to guide each structure’s preservation and interpretation plan. Preserving these sites saves a tangible connection to the past and ensures their stories can continue to be told.

Curious to know what stories might be held within the walls of your old home? Our research process, as well as the types of resources and archives used, are described in detail in Preservation Maryland’s Property Research Guide. While not an exhaustive listing of all possible resources, this guide includes the most commonly used materials needed to research the history of your property.

If you’re looking for even more assistance on how to research, then join us on February 8, 2024 for a virtual Researching Your Historic Property webinar.

And if you’re interested in learning more about the resources held at the Maryland State Archives, save the date for March 20th and join us for a public tour!

Sources:

FamilySearch.Org

Census Data

Frederick County Circuit Court

Deeds, Wills

Library of Congress

Sanborn Maps

Maryland State Archives

Tax Assessments, Plat Maps

MDLANDREC

Deeds, Plat Maps

Newspapers

The Baltimore Sun, The News, The Frederick Post, The Brunswick Citizen

National Archives

Census Data