On February 28, 1827, Maryland merchants and bankers came together to charter the Baltimore and Ohio (B&O) Railroad. The oldest railroad in the United States, the B&O Railroad connected over thirteen states with rail lines. This railroad was the first common carrier line in the country, transporting passengers and goods for a fee. Although it was chartered in 1827, construction for the railroad did not begin until July 4 the following year. The B&O railroad was revolutionary for its time, crossing numerous rivers and laying tracks on undeveloped land; in total, the railroad spanned 4,535 miles. It also played a crucial role in the Civil War, as the Union used the lines to ship supplies to hundreds of its troops across various states. The B&O company operated from 1828-1987 — a total of 159 years.

The B&O railroad brought much industrial growth to Maryland. In Baltimore, numerous industries opened up around the tracks. Construction shops for steam engines, repair sites, iron works, blacksmiths, sawmills — all appeared in railroad towns. With the opening of these businesses came more job opportunities for many Marylanders. Particularly, Irish and German immigrants flocked en masse to Baltimore to find railroad work; they helped construct the rail lines, working around the clock in dangerous conditions to meet the deadlines. In 1843, Congress allocated $30,000 to the construction of a telegraph line along the railway, connecting Washington D.C. to Baltimore and improving communication between the two cities. The B&O railroad was transformative for that reason and many others.

The B&O railroad brought much industrial growth to Maryland. In Baltimore, numerous industries opened up around the tracks. Construction shops for steam engines, repair sites, iron works, blacksmiths, sawmills — all appeared in railroad towns. With the opening of these businesses came more job opportunities for many Marylanders. Particularly, Irish and German immigrants flocked en masse to Baltimore to find railroad work; they helped construct the rail lines, working around the clock in dangerous conditions to meet the deadlines. In 1843, Congress allocated $30,000 to the construction of a telegraph line along the railway, connecting Washington D.C. to Baltimore and improving communication between the two cities. The B&O railroad was transformative for that reason and many others.

To celebrate this anniversary, Public History and Communications intern Allyn Lawrence visited one of Maryland’s many unique train museums. Read below for her experience at The Baltimore and Ohio Station Museum in Ellicott City, Maryland:

Station Entry

The Ellicott City Station is the oldest surviving railroad depot in the United States, and one of the oldest in the world. Built in 1831, the Ellicott City depot connected thirteen miles of track between Baltimore and Ellicott’s Mills, Maryland. Located in Historic Ellicott City, the museum itself resides in the old station building, where visitors can explore the various exhibits. One can also enter the freight house — where there is a model train setup, a replica of the thirteen miles of track and the surrounding lands — and a train caboose that was used on the B&O railroad decades ago. Admission is free, and the museum is well-worth a visit!

Each room of the museum is captivating. The first room off the left of the entrance resembles the freight agent’s living quarters. The first agent hired at the Ellicott’s Mills depot was Samuel Smith. In 1830, he began living full-time at the station for $400/year, supervising the station, handling cargo, and selling tickets. Signs along the wall in the room explain that the placing of the depot in Ellicott’s Mills was purposeful. The Ellicott family, who had a big milling industry in the area, donated 52,125 square ft. of land to the B&O company and allowed miners to quarry granite from their quarries for free. At that time, they realized that the railroad would bring much business to their mill, so they wanted the station built in their town. They were right: the railroad transformed the town. After the station was constructed, more shops, schools, and hotels opened up in Ellicott’s Mills.

Telegraph Stamps

Telegraph Room

Other rooms in the museum exhibit different technologies used by the B&O company. The telegraph room displays old-fashioned telegrams used by operators on the B&O railroad. The telegraph lines that were laid alongside the tracks allowed the news of the start of the Civil War to reach President Abraham Lincoln in 1861. Telegrams sent by train needed special telegraph stamps. Similar to postage stamps, telegraph stamps were a form of payment for sending the message. Today, many of the remaining telegraph stamps are unused, because stamps that were pasted to the telegraph form had to be destroyed for privacy reasons

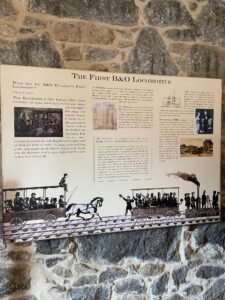

One of the most interesting pieces of information I learned was that the first B&O railroad trains were pulled by horses.

Steam engines were not incorporated into the design until the mid-1830s. After the original tracks were laid, horses could travel on them. One horse could pull three loaded cars, a weight of about 16,200 pounds! A passenger car pulled by horse could make the thirteen-mile trip from Baltimore to Ellicott’s Mills in an hour and a half. A volunteer at the museum explained to me that the railroad replaced the horses every seven or eight miles in order to maximize efficiency. A stable was constructed a few miles away from the depot to house the horses that the B&O used.

Rail Car

I recommend going inside the freight house and the caboose after you are finished exploring the main building of the museum. The model train setup was awesome. It paints a nice picture of what the railroad looked like running through Ellicott City and Baltimore. Small children will surely be entertained by the tiny trains running along the trucks. Walking through the caboose was the most interactive experience. You open the door to enter the car, and it felt like you were actually on the train and hopping to another car. In the caboose, there is a sink that was used by the railroad operators; you can also sit on the seats, which were actually pretty comfortable.

The Baltimore and Ohio Station Museum in Ellicott City, Maryland is the perfect example of why we need to preserve Maryland’s history and heritage. This depot might not have been the first railroad station constructed in the United States, but it is the oldest surviving depot. The depot might have been torn down in the 1970s if it were not for the combined efforts of Howard County Recreation and Parks, Preservation Maryland, and Historic Ellicott City, Inc. When enough money was raised, the depot remained standing and was converted into a museum. Now, visitors to the museum can learn all about the importance of the B&O railroad in Maryland’s history.

Our New property redevelopment work in Ellicott City

Content for this blog was researched and compiled by Allyn Lawrence, Preservation Maryland’s Spring 2022 Public History and Communications Intern. Working through the Waxter Intern Program, Allyn composes articles on topics relating to Maryland’s history and culture. She is a recent graduate of Towson University.