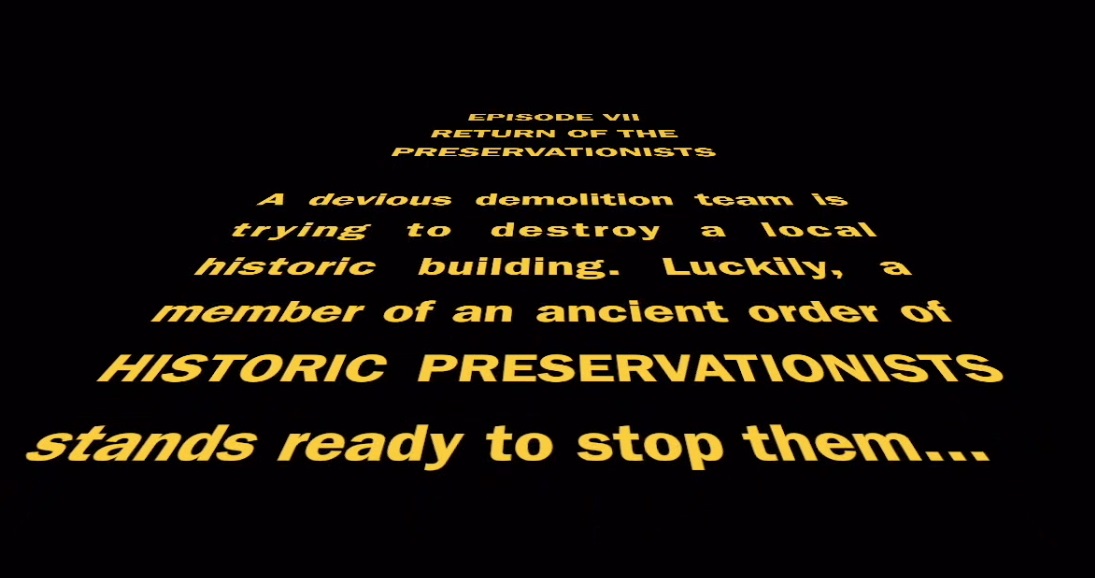

You might be wondering why we’re doing a Star Wars post today; we recommend looking at the calendar and saying the date out loud. And, of course, reading the rest of this blog:

A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away…

With these words begins one of the most famous films of all time. Star Wars took the world by storm when it was released in 1977. All in all, the film garnered $461 million at the U.S. box office and $314 million abroad. In fact, it was the highest-grossing film of all time until the release of E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial in 1982 and it was nominated for ten Academy Awards, and won seven. So far, there have been six sequel and prequel films with two more planned to be released in December of 2016 and 2017 respectively. Clearly, Star Wars is an important cultural force.

At first glance, the only thing that Star Wars might have in common with historic preservation is that happened a long time ago, but in fact, attempts to preserve Star Wars can lend great insight into cultural property and media archiving.

Due in part to its popularity, Star Wars was one of the first films to be added to the National Film Registry when it opened in 1989. However, as recently as 2014, the Library of Congress had yet to acquire a copy of the original film, or its 1981 sequel, The Empire Strikes Back which was added to the registry in 2010.

As it happens, the original Star Wars films as they were released in theaters are rather difficult to find. In 1997, George Lucas, the creator of the series, released “updated” versions of the original films on VHS, referred to as the Special Edition releases. Later, in 2004 Lucas further edited the films for their DVD release, and did so again in 2011 when the films were released on Blu-Ray. Lucas has stated that his primary motivation for these changes was that he considered the original films unfinished citing a lack of resources and insufficient technology to realize his creative vision when the films were originally made. Lucas has pushed these edited versions of the films to the point that he has referred to the theatrical releases as the “rough cuts” of the films and the later releases as “final cuts.” The copies of the films have not been given to the Library of Congress, in part because Lucas never felt that they were ready to be preserved.

Passionate fans of the Star Wars series have time and again decried what they perceive as Lucas meddling with their precious childhood memories. This raises a question that preservationists must often face: when does a cultural artifact, be it a building or a film, belong to the owner (or creator) or the community? There is something to be said for Lucas’ artistic prerogative, but how do America’s public archival repositories also serve the millions of viewers that were impacted by the original releases?

Now that Lucas has sold the rights of Star Wars to Disney, the possibility of a re-release of the original theatrical versions of the Star Wars films is more likely than ever before, but it is clear that preservation is a very important issue even in a galaxy far, far away.

This Preservation Month post was written by Benjamin Israel. As an intern with Preservation Maryland, Ben developed and deployed our current digital archive workflow, and processed over 1500 photos from our collection that are now available on Flickr. He is graduate of St. Mary’s College of Maryland. Learn more about Ben and our intern program here: presmd.org/waxter.