It’s the first day of National Oyster Week, and the Chesapeake’s brackish waters are home to millions of the mollusca. Important to Maryland’s cultural heritage and economic vitality, oysters also had a role in many historic buildings and in historic preservation. And to add a little adventure into the oyster’s local lore…have you heard of the Oyster Wars?

Global History, and Maryland Watermen

The Romans were the first group to cultivate oysters. Using the practice we now call aquaculture, Romans were able to collect oyster pearls, shells, and meat in high quantities. The French and English also farmed oysters, and in the 1800s a Frenchman by the name of Monsieur de Bon came up with a technique to re-seed oysters: collect the spawn and replant them in the oyster beds. Oyster fishing also played a vital role in North America: once European colonists immigrated to the United States, they took up oyster fishing and it very quickly became a significant contributor to coastal economies.

Maryland’s watermen have made a living harvesting oysters for centuries. In the 1850s it is estimated that more than 1.5 million bushels of oysters were harvested from the Chesapeake Bay each year, and by the 1900s the Chesapeake Bay’s oyster fishery was one of the most important in the entire nation and contributed millions of dollars to the region’s economy. Adding to the state’s cultural heritage, skipjacks were specifically designed for dredging oysters. From a conservation prospective, oysters improve water quality and oyster reefs provide valuable habitat, food, and protection for other marine species.

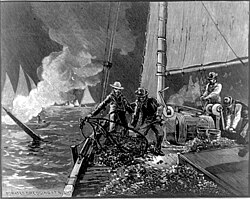

Oyster Wars

In an interesting piece of Maryland oyster history, the Maryland General Assembly would pass legislation in the 1830s which allowed only state residents to harvest oysters in its waters and while neighboring state Virginia allowed dredging, Maryland did not, causing tension and sometimes violent clashes when the boundaries were ignored. In the 1880s the industry was booming but local oyster beds had been depleted, which prompted clashes between local fisherman, as well as with out-of-state fishermen. In 1868 Maryland founded the “Maryland Oyster Police Force,” charged with enforcing harvesting laws, which was also met with hostility from armed watermen, both poachers and legal watermen. More about the Oyster Wars from our partners at the Maryland Department of Natural Resources: Oyster Wars: The Historic Fight for the Bay’s Riches

Preserving Resources: Oyster Recovery

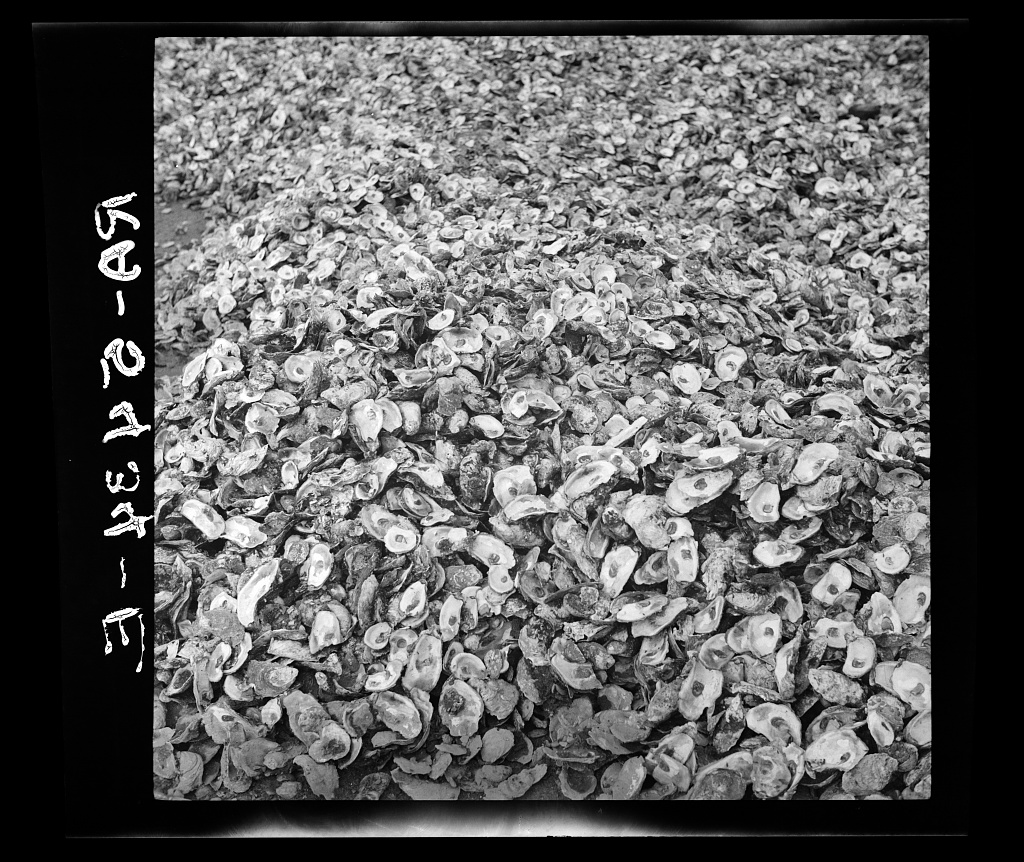

After overfishing, habitat loss, and disease contributed to staggering oyster loss, the Oyster Recovery Partnership made the commitment to restore native oyster population by “building sanctuary reefs, rebuilding public fishery reefs, supporting the aquaculture (oyster farming) industry, recycling oyster shell, and getting the public involved through hands-on volunteering and events.” Today, billions of oysters have been planted in the Bay.

Planting 1.7 billion oysters this year shows the success of the broad partnership of watermen, scientists, academics, nonprofits, and state and federal government officials dedicated to this vital natural resource and economic driver for Maryland. I’d like to thank the partner organizations and our dedicated Department of Natural Resources staff who enabled the state to achieve this significant accomplishment.”

– Maryland Governor Wes Moore, 2023

In Construction/Oyster Slaking

Oysters weren’t just food, their shells were used for lime, an important ingredient in fertilizer and construction materials in the mid-1600s. Burnt oyster shells were turned into powdered lime to use in mortar and concrete.

See more of that process here: