As work on the Jonathan Street cabin progresses and the once-stripped structure gradually forms into a cozy abode, it seems appropriate to reflect on those who once called 417 home. While not everyone left their marks on the dwelling like H. May, each resident’s time in the cabin is noteworthy.

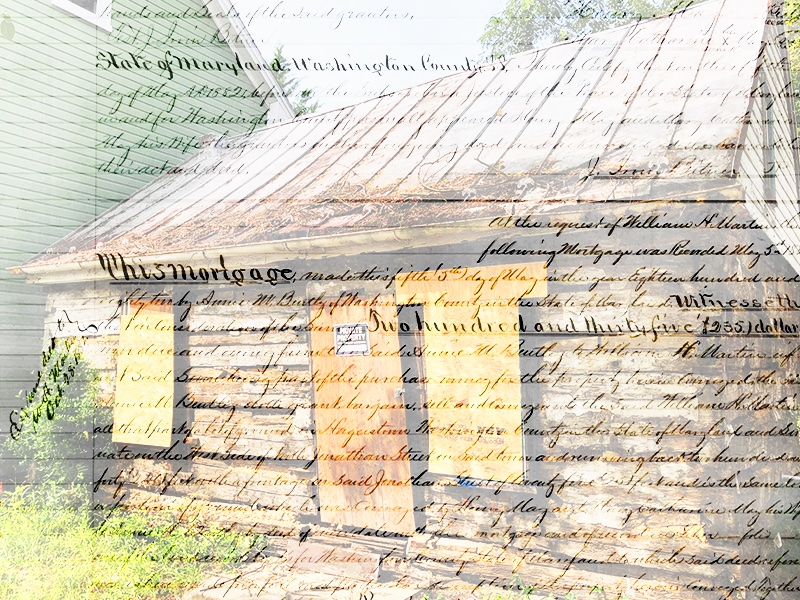

Indeed, the woman to whom the May family sold the house did not leave physical traces of her own occupancy that we know of; nevertheless, it was one of significance. According to a deed recorded in Washington County on May 5, 1882, Henry and Mary Catherine May did:

“grant, bargain, sell and convey in fee unto Annie M. Bentley all that part of a lot of ground in Hagerstown Washington County in the State of Maryland on the West Side of North Jonathan Street in said town … the same portion or lot of ground that was conveyed by Philip Fisher to the said Mary Catherine May by deed dated the 19th day of March AD1872 …”

- Credit: Washington County Circuit Court Land Records Department

- Credit: Washington County Circuit Court Land Records Department

Ms. Annie M. Bentley paid the Mays $500 for the purchase—a full $100 more than Mary Catherine paid 10 years prior and the equivalent of approximately $13,000 today, give or take a few hundred. This made Annie the second female in a row to own the property. But perhaps of even greater significance is that Ms. Bentley was also the first African American to own and reside in the cabin.

Unfortunately, though to no surprise, information on Annie has been a challenge to track down. It is likely that not much documentation remains or even existed in the first place given her status. However, records do show that the same day she acquired the property she mortgaged it to a William H. Martin for $235. It was agreed that the mortgage would be paid back with interest in 12 months, but it would not be until 1884 that it was noted as released. Around that time, 417 left Annie’s possession and would be involved in a lawsuit in Washington County Equity Court for seven years.

- Credit: Advanced Aerial Imaging Concepts / AAIC Visual Perceptions

- Credit: Advanced Aerial Imaging Concepts / AAIC Visual Perceptions

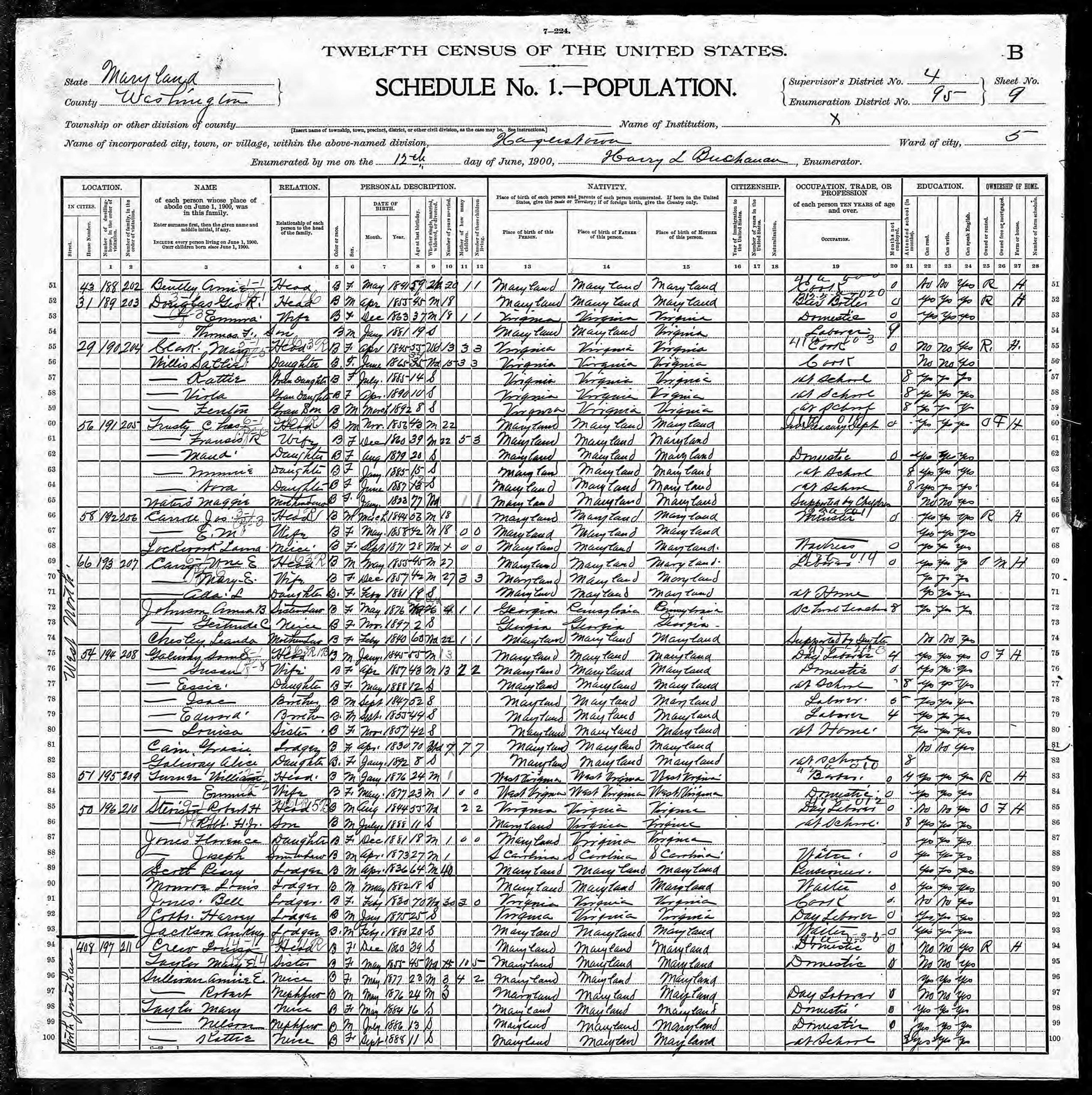

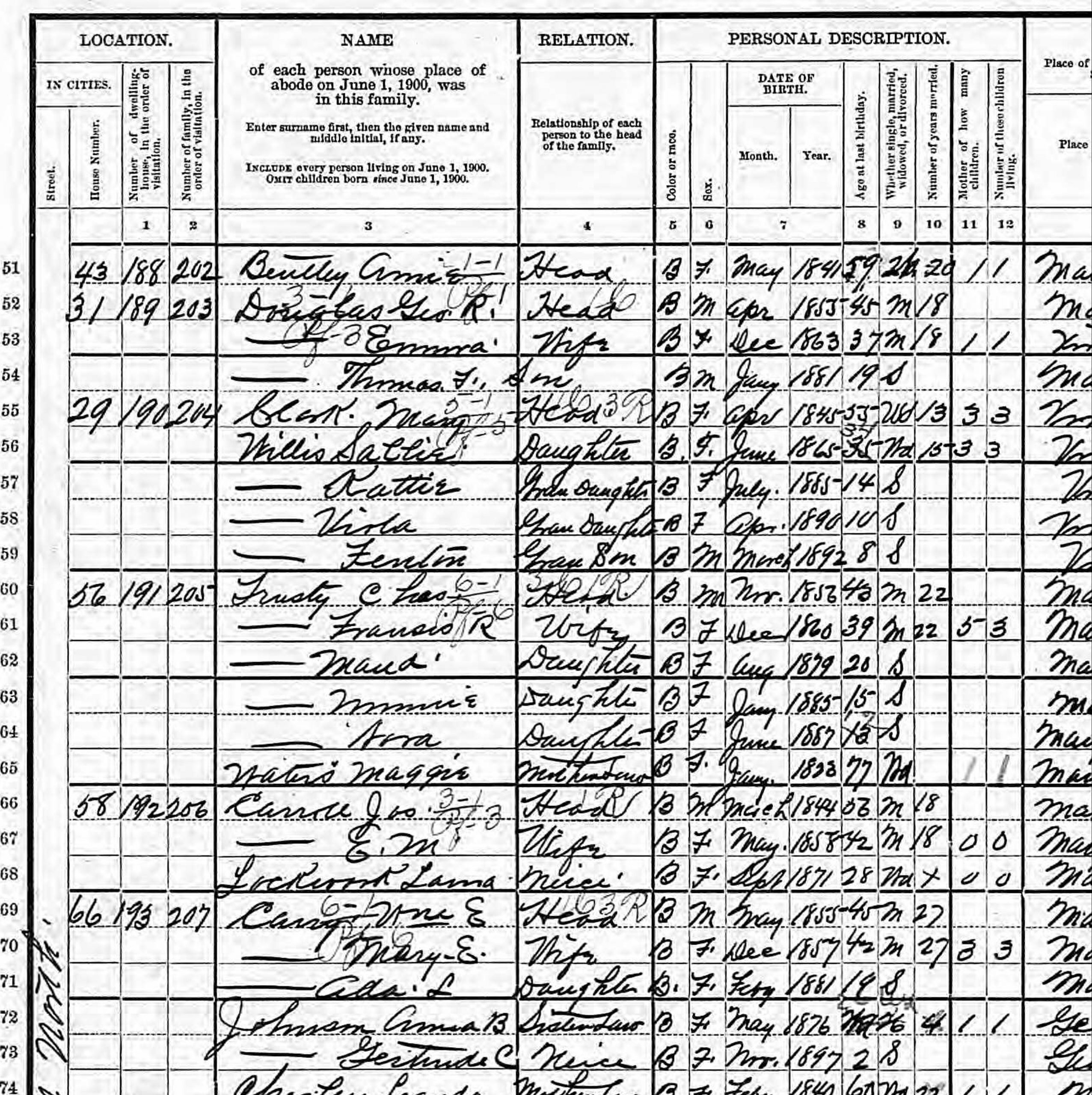

As for who Ms. Bentley was and the life she led, that remains largely unknown to us. She did appear in the Twelfth Census of the United States, recorded June 12, 1900, giving us a bit more insight into her story. The document enumerates that she was born in Maryland in May of 1841 to parents whose places of birth are also listed as Maryland. According to the University of Virginia Library’s Geospatial and Statistical Data Center, in 1840 the number of enslaved African Americans in Washington County was 2,546, while 1,580 were free. By the start of the Civil War two decades later, this rate had reversed so that the Black population comprised a higher number of free individuals than enslaved individuals, but only barely. Not until after slavery was abolished in Maryland on November 1, 1864 would the number finally reach zero. Knowing this, it is not improbable that Annie and her family lived at least part of their lives enslaved, making her purchase of the cabin in 1882 all the more worthy of recognition.

The federal census also tells us that at some point in those tumultuous years, Annie did marry and give birth to one child. Records indicate that Annie and her husband would remain married until his passing after 20 years together. We also know her child made it to adulthood, as he or she was marked as living when the census was conducted in 1900, at which time Annie would have been 59 years of age. She is listed as living alone, having taken up residence just down the block from the Jonathan Street cabin on West North Street. Underneath columns #22 and 23—“Can read” and “Can write,” respectively—the enumerator twice scribbled “no.” She supported herself by working as a cook; no identification of where or for whom is provided.

- Credit: Advanced Aerial Imaging Concepts / AAIC Visual Perceptions

- Credit: Advanced Aerial Imaging Concepts / AAIC Visual Perceptions

The rest of Annie M. Bentley’s life remains a mystery. A deeper investigative dive would be needed to find out more, such as if she lived in Hagerstown her whole life, when she passed away, what family she was survived by, or where she was laid to rest. Even with our limited details, however, one can imagine hers was a life filled with many stories worth telling. And though she was a resident at 417 Jonathan Street for only a short while, her time in the cabin gave it purpose and significance. There’s no doubt the cabin’s story would be incomplete without including her own.

To learn more about the Jonathan Street project and Preservation Maryland’s Historic Property Redevelopment Program, click here.

The project has been made possible by a diverse array of funders from across the region and nation – including numerous individuals, the State of Maryland, the Middendorf Foundation, The 1772 Foundation, the Rural Maryland Council, the Delaplaine Foundation and many corporate partners and sponsors.