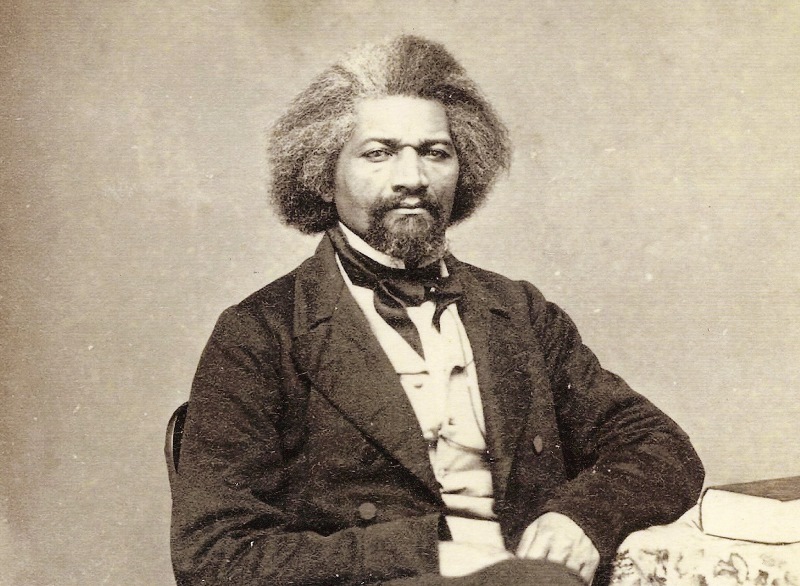

Few names conjure up as much respect, admiration or praise as that of Frederick Douglass. On the anniversary of his death in 1895, Preservation Maryland is proud to remember the contributions of one the state’s most famous citizens.

Unlikely is perhaps the word best used to describe Douglass. His rise from the shackles and putrid oppression of slavery to internationally renowned speaker, orator, and father of civil rights was unlikely — but the improbability of his rise makes his success all the more impressive and remarkable.

Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey was born into a world of slavery on Maryland’s eastern shore in Talbot County. The probable location of his birth — in his grandmother’s cabin on a plantation near Tuckahoe Creek — will soon be dedicated a Talbot County park. Douglass’ true birthday was unknown to him, as it was to many slaves, but he chose to celebrate on February 14th — an early act of self-determination true to his character. Douglass’ own surname was yet another act of self-determination — a name taken after his escape north.

Douglass’ formative years were spent in toil on Maryland’s Eastern Shore. In his autobiographies, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, and an American Slave and My Bondage and My Freedom, Douglass specifically recounts his harrowing years spent on Wye Plantation — a massive plantation with an equally impressive historic home built on the backs of enslaved African labor, like the young Douglass.

It was at Wye where Douglass learned about many of slavery’s most cruel and hateful indignities, including the sadness of why he believed slaves sang. Douglass explained,

I have often been utterly astonished, since I came to the north, to find persons who could speak of the singing, among slaves, as evidence of their contentment and happiness. It is impossible to conceive of a greater mistake. Slaves sing most when they are most unhappy. The songs of the slave represent the sorrows of his heart; and he is relieved by them, only as an aching heart is relieved by its tears. At least, such is my experience. I have often sung to drown my sorrow, but seldom to express my happiness.

Unlike some of Wye’s enslaved laborers, Douglass was not sold south and instead left Wye for Baltimore after beging given to another family. It was there that Douglass secretly learned to read before he was send back to work for Edward Covey back on the Eastern Shore in his teenage years. Covey, a particularly hateful and cruel farmer was known as a “slave breaker” and whipped the teenage Douglass until he fought back. Once Douglass overcame Covey in a physical confrontation the whippings ceased. In 1838, after 20 years of enslavement he escaped to the freedom of the north. Following his escape he sent for Anna Murray, a free-black woman from Baltimore whom he would later marry.

From there, Douglass would go on to the celebrated career for which he is remembered. Preacher, best-selling author, international speaker, political campaigner, civil rights’ advocate, and famed orator. Through it all, despite its wickedness, Douglas would never forget his formative years spent in Maryland. Nineteenth century Maryland — good, bad and ugly — was a critical part of the complex formula which made the man.

As he neared the end of his life, Douglass would return to the region — living out his final days at his handsome estate in the Anacostia neighborhood of Washington, DC. In the twilight of his life, Douglass also worked with his son Charles to establish Highland Beach, a summer resort in Anne Arundel County, Maryland, built exclusively by and for African-Americans. Douglass designed his summer home there, with a high view from which, he said, “I as a free man, could look across the Bay to where I was born a slave.“

Douglass passed away on February 20, 1895. The 77-year-old of unlikely beginnings left the world as perhaps the most influential African-American of the 19th century — and arguably the most famous Marylander ever.