In this edition of the Preservation Playlist, we’re rewinding the track all the way back to the 1930s.

Did you know that June is Black Music Appreciation Month? In 1979, under President Jimmy Carter, the month of June was dedicated to celebrating and appreciating the work of Black musicians in the United States. While Black Music Appreciation Month began in the1970s, Black musicians have made major strides in the music industry throughout all of U.S. history.

In the 1930s, Marylanders witnessed the golden age of music. The radio introduced Americans to a variety of music compared to the previous decades. The nation encountered a sweeping cultural and economic shift. In the 1920s, jazz and blues were viewed as mature, sophisticated music genres geared towards the white upper-class consumption. However, in the 1930s, these musical forms turned into a sweeter sound for all races and social statuses to enjoy. The tempo may have shifted, but lyrically the message reflected more racial and historical barriers faced by the African-American community.

From the Great Depression to the start of the Civil Rights Movement era, Black Marylanders listen to music to elevate feelings and emotions. Black music is an act of lamentation, preservation, and celebration of their community. Let’s take a look at how Maryland influence these Black artists to reveal the issues of American traditions and values through music:

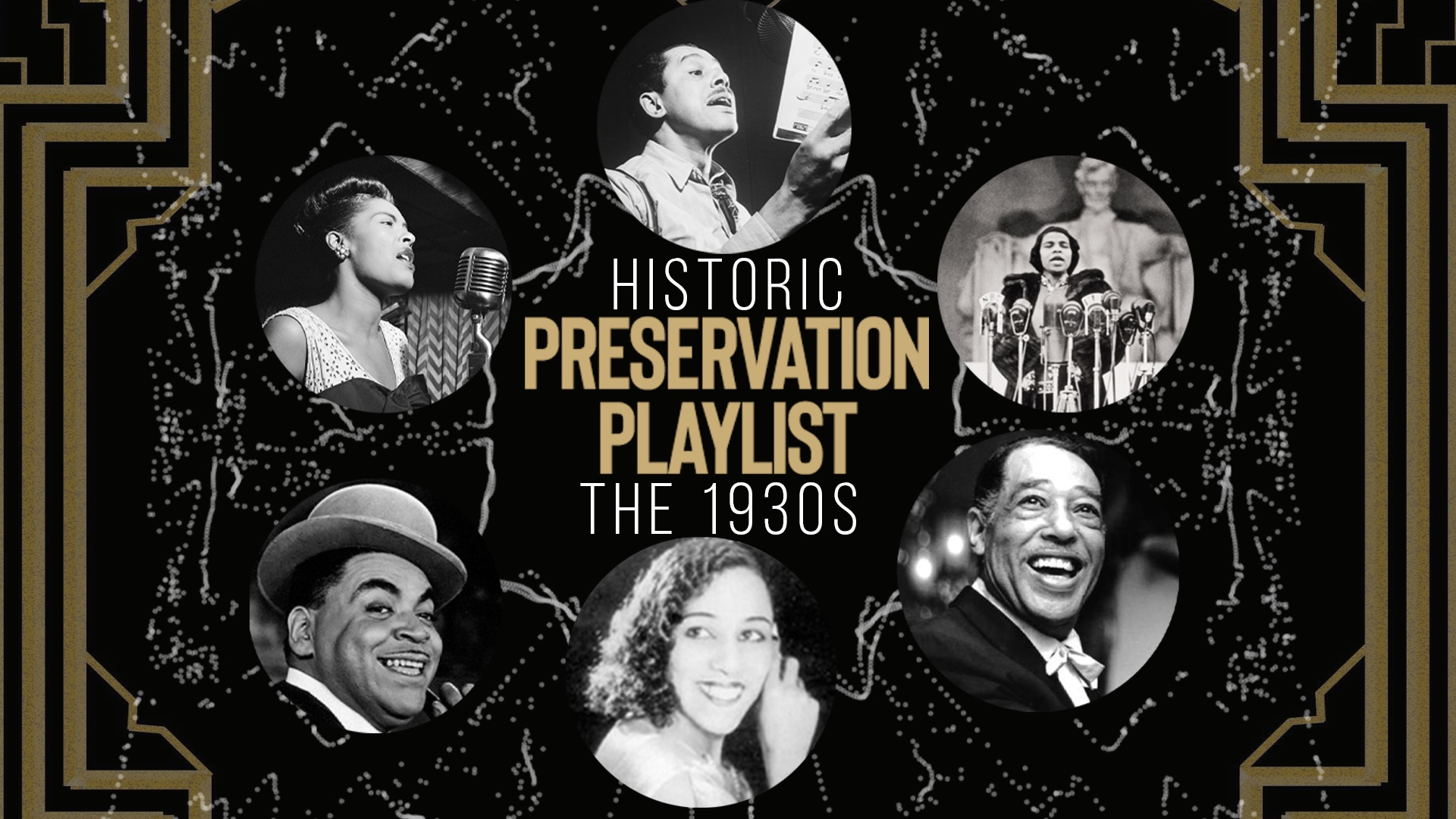

Happy Feet

Cab Calloway & Orchestra

Known as the “Hi De Ho” man, Cab Calloway was the leading showman entertainer of the Swing Era. Originally from Rochester, New York, Calloway spent his childhood in Baltimore, Maryland. He attended Frederick Douglas High School in Maryland, and it played a significant role in his musical career. During his reign, the Great Depression was devastatingly impacting Americans. Calloway had a way for Americans to forget about their woes by getting them to dance and sing away their pain. For instance, in his 1931 song, Happy Feet, Calloway sang:

I can’t control my dancing heels

To save my soul!

Weary Blues

Can’t get into my shoes

Because my shoes refuse

To ever grow weary!

This upbeat song lifted many spirits and financially helped Calloway in this dark time. By the age of 23, Calloway earned around $50,000 per year performing during the Great Depression. Today that salary is worth about $860,000.

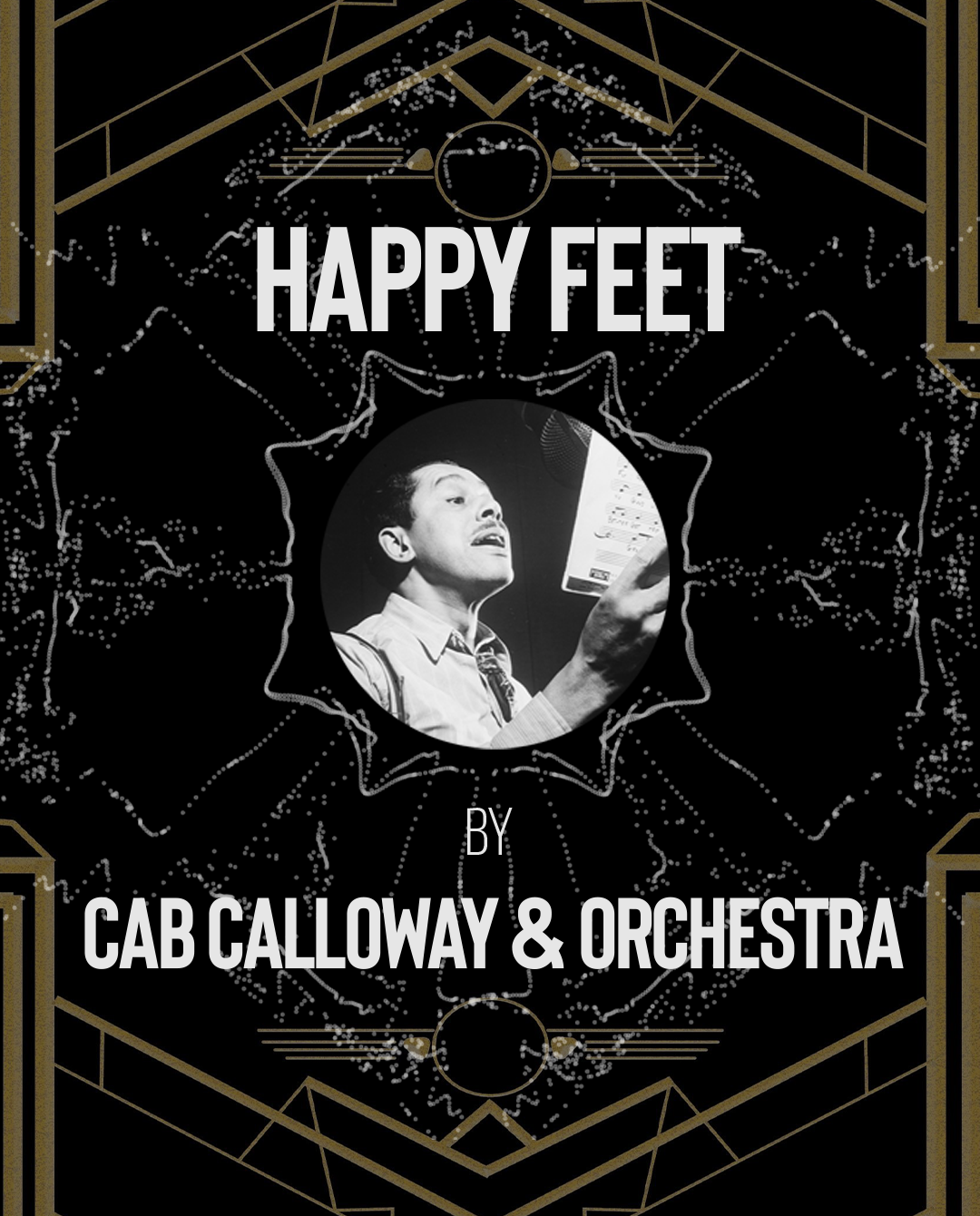

Last Dollar

Blanche Calloway & Her Joy Boys

With a music career that spanned over fifty years, Blanche Calloway was the older sister of Cab Calloway and the first African-American woman to lead an all-male orchestra. Blanche was known for her flamboyant performance style, which contributed to her brother’s career and theatrical performance style. Raised in Baltimore, Blanche started singing at an early age in choir concerts at the local Grace Presbyterian Church in the city.

Additionally, Blanche made her professional debut in Baltimore in 1921 alongside Baltimore native pianist Eubie Blake and Noble Sissle’s musical Shuffle Along. Blanche taught her brother about performing, and the two would occasionally perform together as a brother and sister act. In the song, Last Dollar, Blanche is literally on her last dollar. The Great Depression of the 1930s caused a decrease in migration in the African-American community due to limited employment opportunities. Despite her financial situation, Blanche felt like a rich woman. For instance, Blanche sings:

Oh, what luck, just one more buck,

Fortune left me by chance

Here’s a bill,

Feel like a mill’

You can tell by a glance

Others may have thought Blanche was crazy to react in this manner. However, Blanche merely thought she was fortunate to have this little bit of money, especially during this challenging time. Blanche did not have the same success compared to her younger brother, but she inspired increased numbers of African-American female band leaders and artists for future generations.

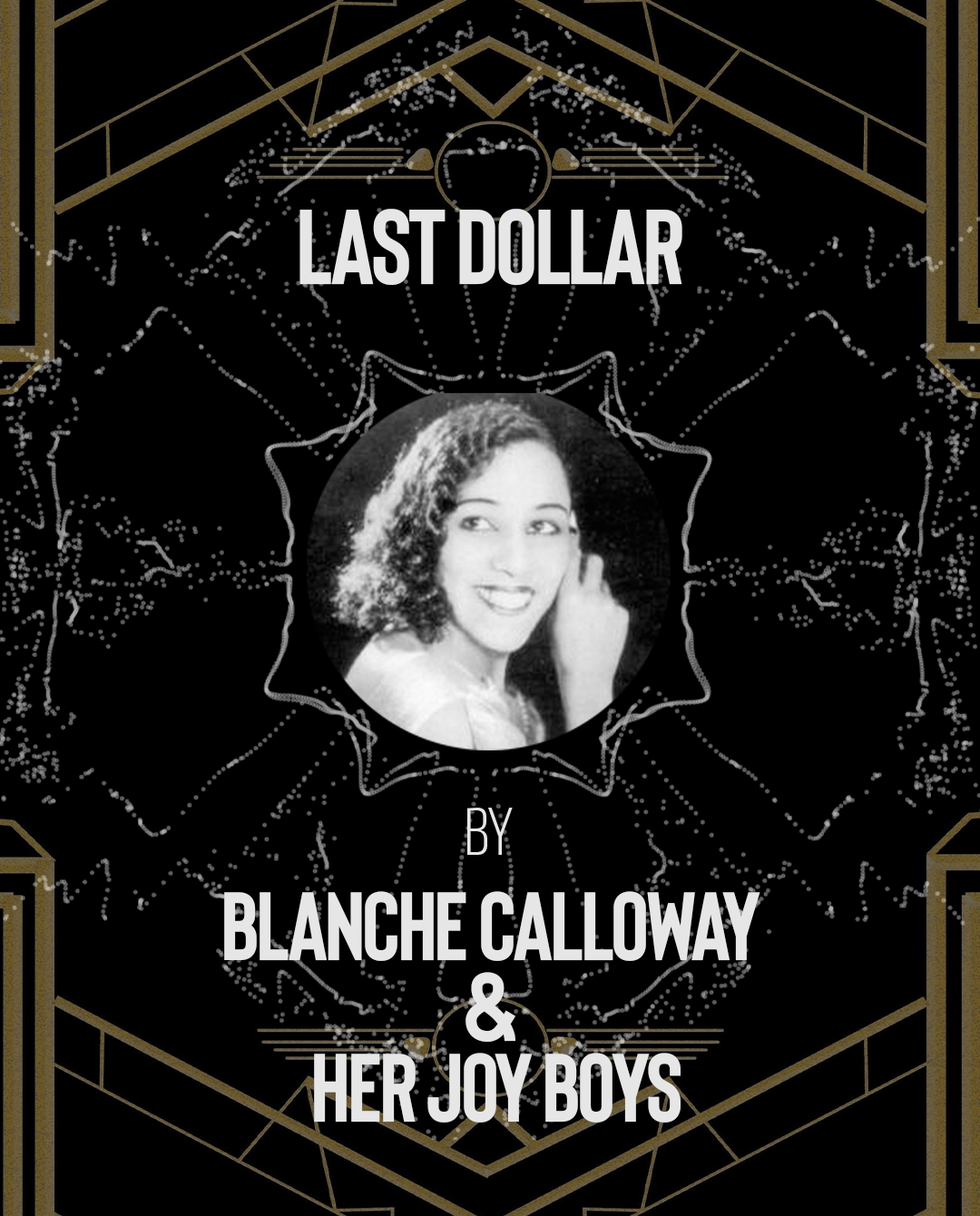

I’m Gonna Sit Right Down and Write Myself a Letter

Fats Waller

By 1935, Jazz pianist Fats Waller’s fame was spreading throughout the nation. He appeared in Hollywood musical comedy films like, Hooray for Love! and King of Burlesque. Although these films highlighted his comedic persona, Waller wanted to be seen as a serious artist. In the 1930s, African-American actors appeared more on-screen in Hollywood films; however, the roles were limited. Black actors had two options— comedic relief or an extra. The casting requirements for Black actors were to have some rhythm and carry an off-key tune of he-de-he-de-hi-de-ho.

Later, Wallers released the song, I’m Gonna Sit Right Down and Write Myself a Letter. In this song, Waller is writing himself a love letter as a lover. Only his lover’s words can encourage him during this time. This song could represent lost love or finding love within yourself. Several artists have performed this song, but Waller’s version remains the most popular version, charting at #3 in Billboard Magazine.

Additionally, Waller worked as accompanist in The Royal Theatre. Located at 1329 Pennsylvania Avenue in Baltimore, Maryland, it first opened in 1922 as the black-owned Douglass Theatre. It was the most well-known theater along West Baltimore City‘s Pennsylvania Avenue and became a frequent home to popular Black entertainment Jazz and Blues artists, some including Cab Calloway, Ethel Waters, Louis Armstrong, and Duke Ellington.

LISTEN TO i’m gonna sit right down and write myself a letter

Take the “A” Train

Duke Ellington

The New York City subway line, the “A” train, brought people from Harlem into Manhattan in the late 1930s. This system provided residential opportunities for African Americans in different parts of the city. Between 1910 and 1930, the African-American population increased forty percent in Northern states. This was due to the Great Migration, which largely took place in major metropolitan cities. Initially, Ellington wrote Take the ‘A’ Train as directions to his apartment for his collaborator and longtime friend, Billy Strayhorn. Strayhorn took the information and made it into a swing song. Take the ‘A’ Train became the opening song at all of his concerts. It also unofficially became the anthem for the NYC Subway Transit system.

Originally from Washington D.C., Ellington was a frequent performer in Maryland entertainment hub circuits, such as the Royal Theatre, Hippodrome, Carlin’s Park, and the Regent Theatre. While the Royal Theater was a popular spot in Baltimore for many of the top African-American entertainers of the era, the Regent was the largest Black-only theatre. Regent Theatre was owned by Louis Hornstein, a white businessman who owned several Black-only theatres in Maryland. He set high standards in business and refused to accept any individuals who made disparaging comments to African-Americans. With these standards, Regent Theatre attracted frequent live performances from Ellington, as well as a boxing exhibition of Jack Johnson, the first African-American heavyweight world champion.

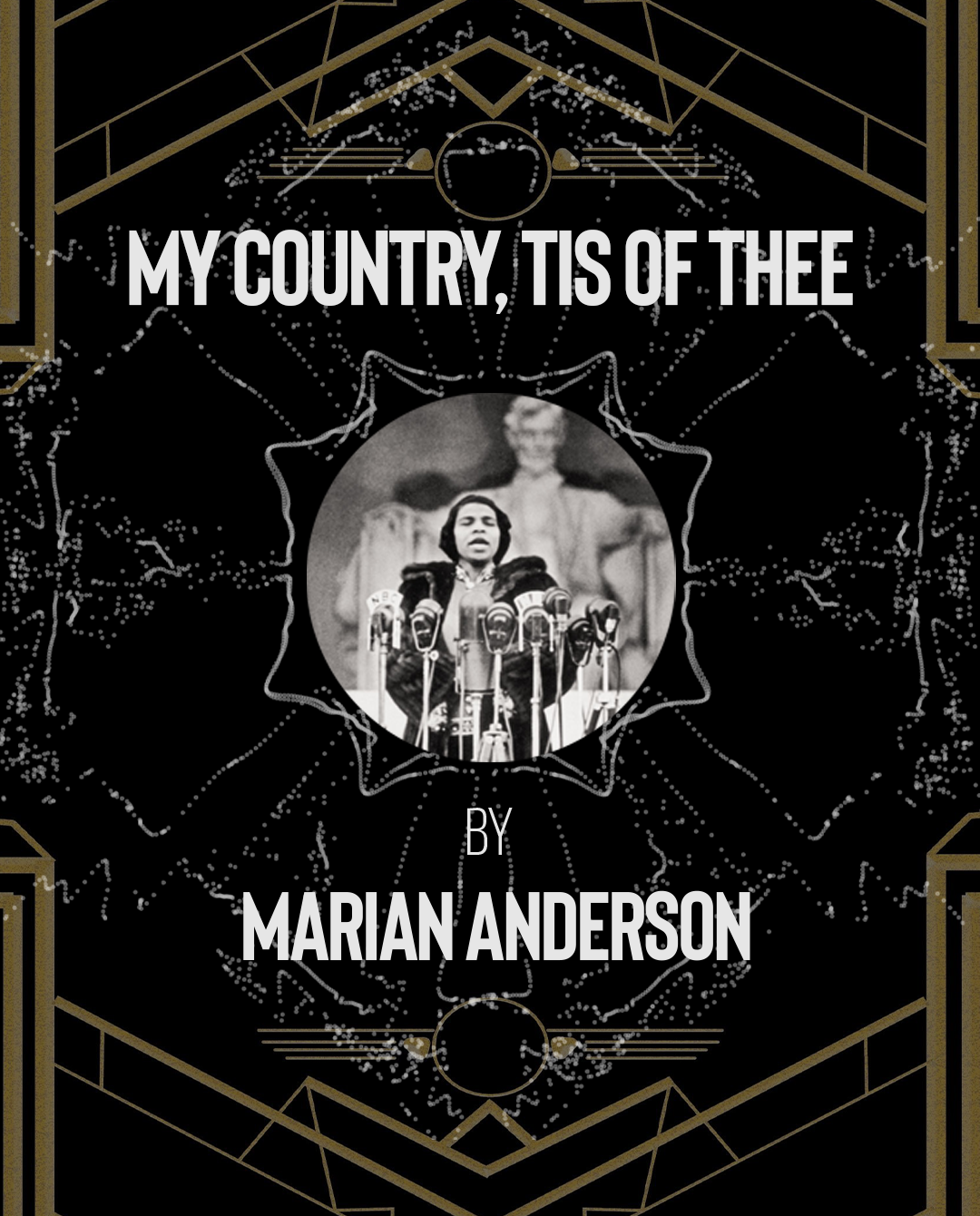

My Country, Tis of Thee

Marian Anderson

In 1939, the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) refused to allow Marian Anderson to sing to an integrated audience in Constitution Hall in Washington, D.C. With the assistance of First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt and President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Anderson held an outdoor concert in the front steps of the Lincoln Memorial on April 9, 1939. She sang to an integrated crowd of over 75,000 people and a radio audience in the millions.

The first song Anderson performed was My Country, Tis of Thee. When she got to the third line, she changed the line from “of thee I sing” to “of thee we sing”. This small change conveys that “we” as a nation have a responsibility to fight against racial segregation. At the age of 89, Anderson was the first American inaugurated in the Vocal Arts Congress. She was honored for this award and attended a vocal competition named after her at the University of Maryland at College Park in 1991.

LISTEN TO my country, tis of thee

Strange Fruit

Billie Holiday

Raised in East Baltimore, “Lady Day,” known as Billie Holiday, sang music that gave rich credibility to the Black experience. Holiday had a traumatic and challenging upbringing that can be felt in her music. While she typically performed break-up ballads, in 1939 she sang a protest anthem about lynching. In the Reconstruction Era, lynching was a common practice to terrorize and control the African-American community. However, in the 20th century, lynching had reached its peaked in the South. Originally a poem by Abel Meeropol, the lyrics of Strange Fruit compared the victims as fruit hanging from trees.

Holiday released this song ten days after Marian Anderson performed at the Lincoln Memorial. This song became a political and emotional weapon in fueling the start of the Civil Rights Movement. As for Holiday, many individuals believe this song is responsible for her run-ins with the law and demise. Despite the outcome, Holiday has left a lasting legacy in the music industry and in Maryland.

In 1985, an eight-foot six-inch tall bronze statue, created by James Early Reid, was first dedicated to Holiday. The statue was placed in a plain cement base due to inflation cost. After 24 years, it was replaced with a suitable pedestal in a rededication ceremony on July 16, 2009. The statue depicts Lady Day in the middle of performing, wearing a strapless evening gown, with her iconic gardenia flower in her pulled-back hair. Her biography is inscribed on the granite pedestal with two sculptural panels inspired by her lyrics in God Bless the Child and Strange Fruit. The God Bless the Child panel depicts a newborn baby. The Strange Fruit panel shows a mutilated man, referring to the lynching during the Jim Crow era.