In late June of 1863, nearly 150,000 soldiers moved through the narrow and dusty roads of Maryland towards the devastating clash at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, just a few miles north of the Mason-Dixon line.

While the battle unfolded on the fields surrounding Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, much of the campaign that led to the dramatic battle played out in Maryland – with both US and Confederate forces moving across the state and covering their movements as they attempted to outflank and corner their adversary.

The Gettysburg Campaign Unfolds in Maryland

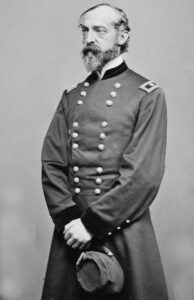

George Meade

Several notable and critical moments of the Gettysburg Campaign unfolded in Maryland itself, including the promotion of Union General George Meade to Major General, Commanding the Army of the Potomac. It was in a farm field beside the historic Prospect Hall, where Meade was awakened in his tent early at roughly 3AM on the morning of June 28th and notified by a courier from President Lincoln that he was to take command of the nearly 100,000-man army. Just three days later, Meade would lead his new command through the largest and bloodiest battle of the war – a baptism of fire perhaps unequaled for a new army commander.

Today, a marker erected in the 1930s, marks the spot near Frederick where Meade learned of his new command – the marker itself is stone from near the iconic Devil’s Den portion of the Gettysburg battlefield.

On June 29th, in nearby Westminster, Maryland, confederate cavalry clashed with US Army horse soldiers in what is referred to as the Battle of Westminster or “Corbitt’s Charge.” The clash, which occurred on the edge of town, near today’s intersection of East Main Street and Washington Road, was small by comparison – but ultimately delayed confederate cavalry from rejoining the main Confederate army at Gettysburg in a timely fashion, thus leaving the rebel army without its eyes as it felt its way toward the enemy.

Westminster and the ridges surrounding it were also where General George Meade expected and planned for the battle to unfold. Meade ordered his engineers to prepare a line of defense, known to history as the “Pipe Creek Line,” for the natural feature which it followed. Ultimately, the battle began in nearby Pennsylvania instead – a “meeting engagement,” which was not entirely planned but evolved as the two armies probed each other and engaged increasingly larger forces. Had the battle not begun in Pennsylvania and Meade’s plan executed instead, today Westminster might hold claim to the largest clash in American history.

In addition to the military maneuvers unfolding in Maryland, the effect of the Rebel army on the civilian population was profound – including the heinous capture of free African Americans in both Maryland and Pennsylvania who were sent south to be enslaved and put in service to the confederacy. Although exact numbers do not exist – obscured by the passage of time and poor record keeping of an army on campaign, the latest research in the field suggests that “the seizure of free blacks and escaped slaves by the Army of Northern Virginia was widespread, systematic, and countenanced by officers up to the highest levels of command.” This moment in the campaign, remains one of the most disagreeable and disconcerting of the entire bloody and dismal affair.

Scene behind the breastworks on Culps Hill, morning of July 3rd 1863, painting by Edwin Forbes.

“…Ah! it was a sad, sad day that brought sorrow to many a poor Maryland mother’s heart.” – Maj. W. W. Goldsborough

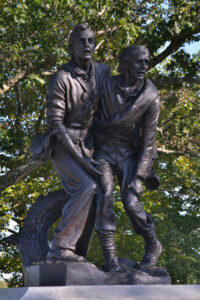

Maryland Monument at Gettysburg

As the armies crossed into Pennsylvania, Maryland continued to play a role – with nearly 3,000 Marylanders fighting in the battle – uniquely with regiments in both the US and Confederate armies. At Culp’s Hill, on the second day of battle, Maryland soldiers from the US and Confederate armies engaged in combat against each other when elements of the 1st Maryland Infantry attacked within 30 yards of the Union’s 1st Maryland, Potomac Home Brigade. Today, the service of both Union and Confederate Marylanders is honored in monuments across the battlefield, including the Maryland State Monument located near Ziegler’s Grove, which was erected in 1994.

A Vast Sea of Misery: The Aftermath of Battle

When the guns fell silent on July 3, the impact of the battle was just beginning to resonate. From the massive human toll to the bloody mess – the armies left behind an indelible and enduring impact on the entire region. Seriously wounded remained at Gettysburg for months – while those able to be relocated found their way to hospitals and railway depots in both Maryland and beyond – including the larger hospitals erected by the federal government at Frederick and much farther south at Point Lookout in St. Mary’s County, Maryland. It was also at Point Lookout where Confederate prisoners taken at Gettysburg were housed until paroled or exchanged.

Gettysburg’s Soldiers National Cemetery

Nearly 160 years later, the Battle of Gettysburg continues to resonate and hold a profound place in the history of a nation still grappling with the legacy of its civil war. At the Gettysburg Soldier’s National Cemetery, Maryland soldiers along with many others, casualties of the three day clash, lie in quiet repose on “fame’s eternal camping ground” – a solemn and powerful reminder of the cost of war and division.