As the affordable housing crisis continues across the country, communities are looking everywhere for solutions including places they may never have considered before. Enter YIGBY, short for Yes in God’s Backyard, a growing movement that champions the use of underutilized religious property for housing and community benefit. The challenge is most congregations lack expertise in real estate, zoning, and are reluctant to engage in development or policy reform conversations. YIGBY is a conversation starter with immediate relevancy in Maryland and across the U.S.

What Is YIGBY?

YIGBY is a spin on the Yes in My Backyard (YIMBY) pro-housing movement but specifically focuses on the involvement of faith-based institutions. The movement originated in San Diego, California, where faith leaders collaborated to redevelop lots they owned into housing. In 2019, the San Diego City Council approved a parking reform policy allowing parking lots to be redeveloped as housing. Tom Theisen, a leader with San Diego’s UPLIFT group stated in an article published at the time, “There are 1,100 churches in San Diego County with over 3,000 acres of property…If just 10 percent of those churches, 100 churches, were to build 20-30 units each, we’re talking thousands of units of housing.”

According to Shelly Stackhouse, a senior program manager at Partners for Sacred Places, “Religious institutions are sitting on land and buildings they no longer fully use. They don’t want to sell; they want to serve. But they don’t always know how.” Nationally, an estimated 100,000 churches may close in the coming decades due to declining membership, particularly among small congregations as a 2023 Faith Communities Today national survey showed the median church size is only 60 regular worship participants.

Maryland’s Opportunity

With a deep-rooted religious history, this idea that faith-based properties could make a dent in the housing crisis is highly relevant. Founded as a colony for Catholics facing persecution, Maryland became a haven for a diverse array of denominations including Catholic, Episcopal, Lutheran, and AME traditions over time. While Christian-affiliated properties are the largest share, according to the Pew Research Center’s 2023-2024 Religious Landscape Study, Maryland is also home to a significant number of synagogues and mosques with roughly 3 % of adults identifying as Jewish and 4 % as Muslim statewide. This diverse legacy has left a significant footprint of faith-owned land and buildings across the state. With news of the Archdiocese of Baltimore’s “Seek the City” closure of nearly half its city parishes, and research shows the percentage of people in the Baltimore metro area identifying as Christian dropped from 67% to 54% over the last ten years, similar to national trends, it’s clear Maryland has faith-owned spaces or land to leverage for housing.

A church and vacant rowhouses on Carrollton Ave in Baltimore as seen in 2018. Photo by Eli Pousson, April 5, 2018, Baltimore Heritage Flickr.

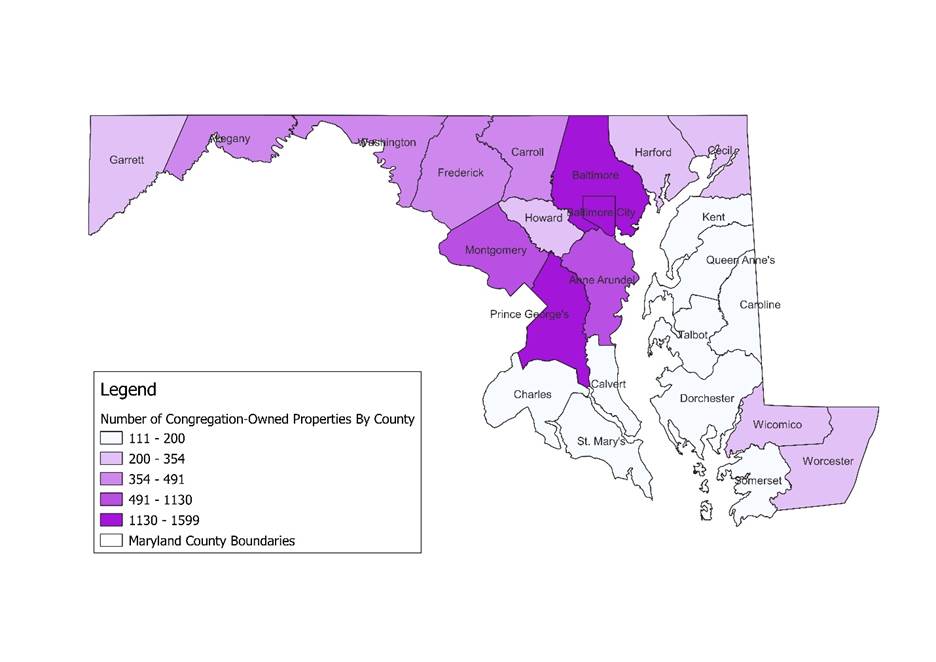

Using the State’s Open Data Portal, Smart Growth Maryland staff determined there are over 11,000 properties that are faith-based exempt properties, cumulating in nearly 37,000 acres. The cities of Baltimore, Silver Spring, Cumberland have the largest number of congregation-owned properties, while Silver Spring, Upper Marlborough, and Germantown have the most acres of congregation-owned land. There are still many research questions to be answered, such as how much of that land is already on public infrastructure that may be appropriate for housing, or nearby to transit and jobs, or how much is zoned for housing.

A map of the number of religious owned properties shaded by county in Maryland. Map by Smart Growth Maryland, data sourced from the Parcel Points layer, Maryland Open Data Portal.

But if just 10% of those acres were developed or repurposed with a medium density (15-20 housing units per acre such as single-family, duplexes, rowhouses, or small apartments) that would result in 16,000-22,000 housing units for Maryland. While that is only 8% of the state’s estimated 275,000 unit shortage, it’s a solution that should not be overlooked.

National Models of Faith-Led Development

The ways in which faith-owned land or buildings could be utilized for housing are wide ranging, from a parking lot turned into homes, extra land built out as apartments, sanctuary adapted to housing, and even fellowship and classroom spaces into apartments. Below are a few examples from across the country:

- In Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the Old First Reformed United Church of Christ transformed a small church-owned parking lot and adjacent lot into 34 units of supportive housing for people previously experiencing homelessness. The congregation even moved a historic house to make the development work. “It took years and lots of sweat equity,” Stackhouse recalls, “but with the right developer, tax credits, and neighbor support, it didn’t cost the church a lot. It’s the definition of a small site with a big impact.”

- In Washington, D.C., The Residences at the Beacon Center, a collaboration led by Pastor Joe Daniels, Emory United Methodist Church, and The Community Builders Inc,. brought 99 affordable housing units and community-serving retail northwest D.C.. Daniels is now mentoring other African American congregations to follow suit.

- In Evansville, IN, the Zion Evangelical United Church of Christ donated its large building to a nonprofit to be converted into 41 units of housing to help the homeless as the church closed after 175 years.

- In Boise, ID, a former church parking lot was turned into single-family homes.

These examples are being repeated all over and are worth exploring for Maryland. One church in St. Louis converted a four-story education wing—once filled with Sunday school classes, now empty—into housing simply by realizing the infrastructure was already in place. “Every classroom had a bathroom. It didn’t need massive renovation,” Stackhouse of Partners for Sacred Places shared. One of the biggest hurdles is that many congregations aren’t familiar with real estate or zoning issues, and they’re often hesitant to step into development or policy discussions.

The Paul G. Reitz Theater, located in the former St. Paul’s Evangelical Lutheran Church (later Cornerstone Baptist Church) in DuBois, Pennsylvania, as seen in May 2020. Photo by Andre Carrotflower, Wikimedia Images.

Why Maryland Should Care

In Maryland, this opportunity is both promising and challenging. The state’s religious landscape is dominated by Roman Catholic, Lutheran, and Episcopal churches—many of which own large amounts of property. Yet, according to Stackhouse, “working with some of these dioceses is complicated. There’s a reluctance to engage in development, and a lack of internal expertise in zoning, legal, and real estate matters.”

With churches closing, particularly in Baltimore, there’s urgent potential to repurpose these sacred spaces before they fall into disuse. Baltimore’s newly created $3 billion Vacant Home Fund is one example of how public resources are starting to align with the need to repurpose unused properties. Religious-owned properties can—and should—be part of that solution.

A Call to Action

For Maryland to unlock the full potential of YIGBY, we need a coalition approach: supportive policies, philanthropic investment, capacity-building for congregations, and strong community engagement.

Smart Growth Maryland staff are attending the upcoming YIMBYtown Conference in September in Connecticut to present on a YIBGY panel and are planning a follow-up blog. Stay tuned—and start the conversation in your congregation today.

Resources for Maryland Congregations Interested in YIGBY